More articles,

http://www.forbes.com/sites/geoffre...unsustainable-biomedical-research-enterprise/

I think that another problem for grad programs, and their students, is that faculty are reluctant to discuss the poor job prospects as grad students are needed to do the research. Hypercompetitiveness makes the atmosphere toxic in academia and the tenured track faculty don’t really seem to be into teaching as most of the grad students they teach, or mentor, won’t even be in the field in ten years.

http://www.usatoday.com/story/opini...l-research-budget-editorials-debates/8705231/

In this article, Fauci talks about delayed discovery of an “HIV vaccine” (if that’s even possible is unknown), and tackling the rising scourge of drug-resistant organisms. I thought that Obama already pledged $500 million specifically for developing an HIV vaccine? Though, of course, basic science research in immunology unrelated to HIV, might, unexpectedly, provide the understanding needed to develop said vaccine, so Fauci may well have a point.

With regards to the rise of drug-resistant organisms, government funded entities such as the NIH/CDC have placed their hopes in the hands of the drug companies who are now expected to, by and large, deal with this problem from the treatment end.

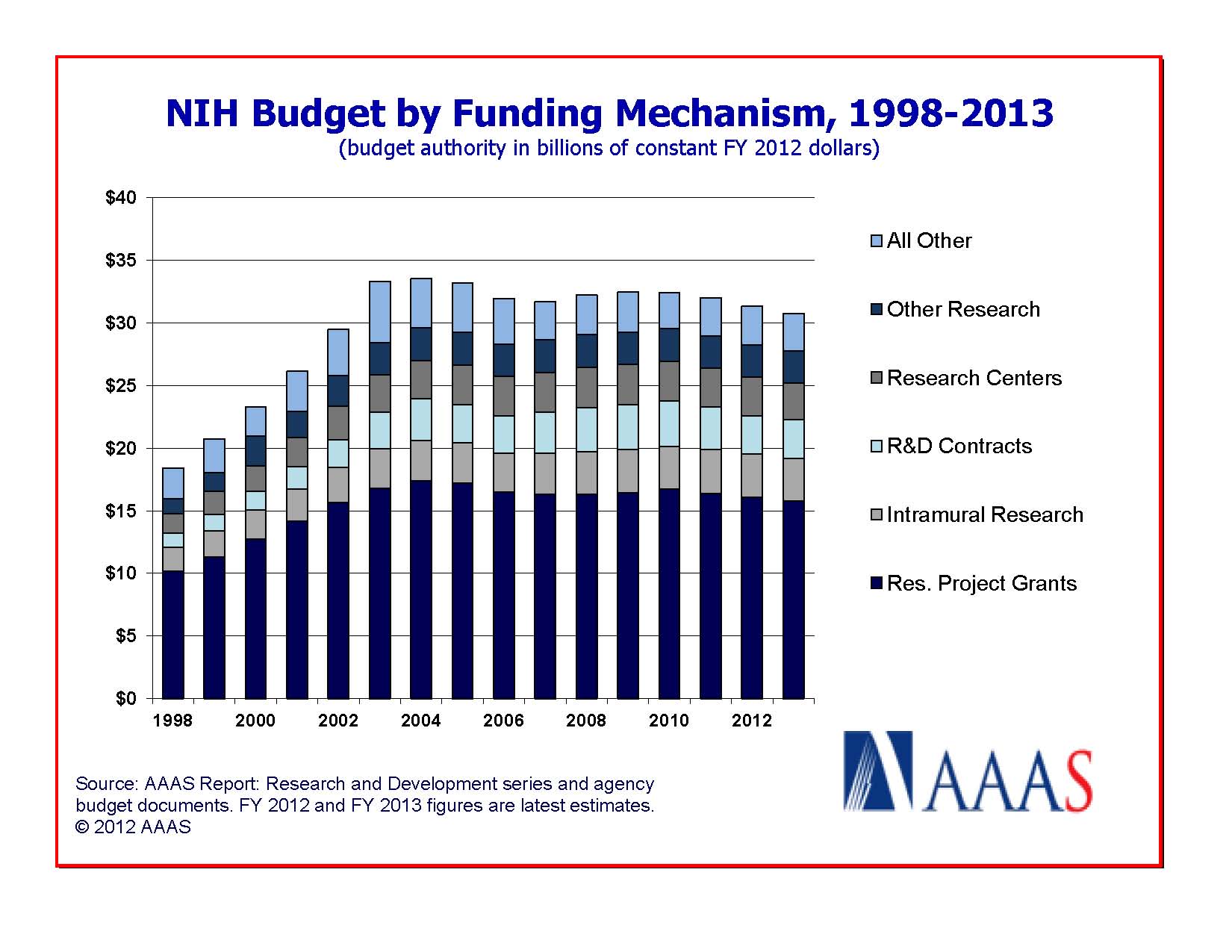

The big players are advocating for modest increase in the NIH budget, but it should be noted that this will do little, if anything, to address demand/supply mismatch between PhDs programs and graduates. It will, of course, help hundreds of already established PIs keep their labs running, and that’s where the budget squeeze really gets the attention of the big cheeses at the NIH, when their friends can’t get the grant to keep their labs open. Other than a small group of retiring big whigs who want to throw a bone to little, and soon-to-be-forgotten, people (the graduate students), and maybe make the system incrementally better for aspiring scientists, the agenda behind raising the NIH budget is helping established investigators.

Also, Collins talks about the amazing research that can’t be funded, but if grad schools are, in some ways, operating a pyramid scheme, and if the brightest students are not going into science, you have to wonder about the quality of research.

Look at the proposals for change, one point advocates encouraging more creative research proposals. If you’re familiar with the current scientific literature, a lot of the stuff being published is derivative, and hyped, and very worrisome—more and more of it can’t be reproduced.

Are staff scientists more efficient than grad students, and worth the higher salary? Given that some foreign grad students come with their own funding, and that most grad students are given a small salary, the current system heavily depends on cheap labor. Take away that cheap labor, and you’ve got less research happening, but perhaps it would be higher quality research if grad school wasn’t the scientific version of the Hunger Games.

The cold machiavellian truth for today's, and aspiring grad students career prospects in academia, would be to hope for a freeze in the NIH budget for the next 6-10 years, overlapping with their training, so that a good portion of the established PIs give up, and retire or switch careers, and that for the NIH budget to increase right during the time they're looking for a faculty appointment. From a societal viewpoint, would this be a good thing? Probably steady growth is the way to go, which the recommendations address:

• Longer-term planning to create more predictable and stable budgets;

• Gradually reducing the number of Ph.D.s in the biomedical sciences by introducing a more selective process for funding graduate students;

• Increasing the ratio of staff scientists to trainees;

• Improving the peer review system to foster the most creative proposals;

• Diversifying graduate education in biomedicine to make students aware of other areas in which they could use their scientific background, such as policy, communications, etc.