- Joined

- Apr 7, 2011

- Messages

- 5,313

- Reaction score

- 1,085

Well there goes the neighborhood

The D.O. Is In Now

Osteopathic Schools Turn Out Nearly a Third of All Med School Grads

By JOSEPH BERGERJULY 29, 2014

Continue reading the main storySlide Show

The D.O. Is In Now

Osteopathic Schools Turn Out Nearly a Third of All Med School Grads

By JOSEPH BERGERJULY 29, 2014

Continue reading the main storySlide Show

- Continue reading the main story

The old Blumstein’s department store sits across 125th Street from the legendary Apollo Theater. It’s something of a Harlem landmark, where “don’t buy where you can’t work” protests led to the hiring of African-Americans as the first salesclerks in 1934 and where the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was stabbed by a mentally unstable woman during a book signing in 1958. Now a row of colorful clothing and jewelry stores lines the ground floor. But the rest of the building has been gutted and fitted with lecture halls, classrooms, laboratories and a library to house the Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Harlem is a fitting location for Touro’s new medical school. Many osteopathic schools have an added mission: to dispatch doctors to poorer neighborhoods and towns most in need of medical care.

“The island of Manhattan has lots of doctors, but not here in Harlem,” said Dr. Robert B. Goldberg, dean of the college, which taught its first class in 2007.

Photo

Students at the Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine in Harlem work on a mannequin with a heart condition. CreditOzier Muhammad/The New York Times

In one classroom, several students lay flat on examining tables while classmates, under the guidance of Dr. Mary Banihashem, worked over their necks. She reminded them to use the patient’s eyes as a reference point in judging alignment as they assess neck motion, “We’re looking for any tenderness” in neck muscles, she said.

Gabrielle Rozenberg, in her second year at Touro, remembers the Ur-moment that would lead her to this somewhat unconventional path in medicine. Growing up on Long Island, she suffered from chronic ear infections. Her doctor recommended surgery. But before committing to an invasive procedure, her parents took her to a D.O. — a physician whose skills are comparable to those of an M.D. In several visits, he performed some twists and turns of her neck and head, and within days the infection cleared up. “The infection happened because of fluid in the ear,” she explained, “and the manipulations opened up the ear canal.” The infection didn’t come back.

Ms. Rozenberg began thinking about one day becoming a doctor of osteopathic medicine herself.

Many are drawn to the field for this more personal, hands-on approach and its emphasis on community medicine and preventive care. There are pragmatic reasons as well. Medical schools are failing to keep pace with the patient population, and competition for careers in medicine is growing fiercer. More students see osteopathy as a sensible alternative to conventional medical school, a way to get a medical education with M.C.A.T. scores that may not make the cut for traditional medical schools. According to the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine, students entering osteopathic schools last year scored, on average, 27, compared to 31 for M.D. matriculants. Incoming M.D. students average a 3.69 grade-point average, versus 3.5 for D.O. matriculants.

Yet it should be noted: Getting into osteopathic school is still excruciatingly tough. Last fall, there were more than 144,000 applications for some 6,400 spots. Touro this year received 6,000 applications for 270 first-year seats for the Manhattan school and a new campus opening this summer in Middletown, N.Y. (The average M.C.A.T. score for students entering this fall was just a point below the M.D. average.)

The boom in osteopathy is striking. In 1980, there were just 14 schools across the country and 4,940 students. Now there are 30 schools, including state universities in New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, West Virginia and Michigan, offering instruction at 40 different locations to more than 23,000 students. Today, osteopathic schools turn out 28 percent of the nation’s medical school graduates.

Whatever the reasons for choosing a D.O. over an M.D., osteopathic medicine has, for decades now and increasingly so, been accepted as authoritative training by the medical establishment, including the residency programs that lead to licensure. This year, more than three-quarters of D.O. graduates successfully “matched” with a residency — half for M.D.-accredited programs and half for D.O.-accredited programs.

That distinction is about to end. In February, the accrediting agencies agreed to a single system for residencies and fellowships. Beginning next year and fully in place by 2020, D.O. residency standards will be aligned with those of the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education, the nonprofit that accredits M.D. programs. The council will now accredit D.O. residencies, though osteopathic representatives will sit on review committees and its board. The announcement cited the need to provide accountability and a uniform path of preparation, and “to help mitigate the primary care physician shortage.” About 60 percent of D.O. graduates go on to primary care fields like internal medicine, pediatrics and family medicine, compared with about 30 percent of M.D.s.

The Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents the 141 accredited M.D. schools, predicts that the Affordable Care Act, providing for federally subsidized health insurance, will add 32 million Americans to the patient population, not to mention the coming eligibility of baby boomers for Medicare. As a result, the country is expected to face a shortage of 45,000 primary care doctors and 46,100 surgeons and specialists by 2020.

Dr. Atul Grover, the association’s chief public policy officer, credits the osteopathic boom to the need for additional sources of medical training. From about 1980 to about 2002, no new M.D. schools opened in the United States. But with the shortage looming, 15 new ones have come on board since 2006. Dr. Grover speculates that the new residency system could also lead to one accreditation for M.D. and D.O. schools. At the least, the new synergy lends an imprimatur to the osteopathic schools, which by and large lack marquee status.

“It will allow graduates from two similar but different education systems to work side by side,” said Dr. John E. Prescott, chief academic officer of the M.D. association. “It’s a true step forward.”

Dr. Goldberg of Touro had this to say: “The merger will let individuals understand that there’s more commonality and strength than there are differences.”

Osteopathic skills were first consolidated by a 19th-century frontier physician, Andrew Taylor Still, who decried the overuse of arsenic, castor oil, opium and elixirs and believed that many diseases had their roots in a disturbed musculo-skeletal system that could be treated hands on. He founded the first osteopathic school in 1892 in Kirksville, Mo. — A.T. Still University. Critics have, from time to time, assailed the techniques as pseudoscience, though the medical establishment has come to accept the approach. And osteopathic schools offer the same academic subjects as traditional medical schools and the same two years of clinical rotations.

Continue reading the main story

The Other Doctors

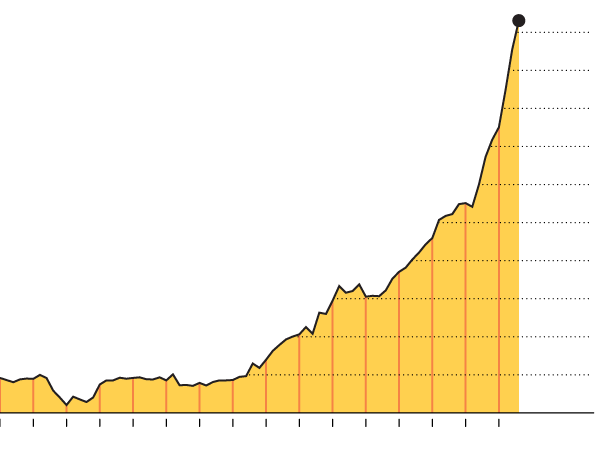

5,154 graduates

2013

5,000

Osteopathic schools turn out 28 percent of the nation’s medical school graduates; 73,000 are now practicing physicians, more than double the number in 1990.

4,000

3,000

2,000

Graduates of osteopathic

medical school

1,000

0

’40

’50

’60

’70

’80

’90

’00

’10

The New York Times

Source: American Osteopathic Association

But an image problem remains. A survey last year by the American Osteopathic Association found that 29 percent of adults were unaware that D.O.s are licensed to practice medicine, 33 percent didn’t know they can prescribe medicine and 63 percent didn’t know they can perform surgery.

Acquaintances would tell Ruchi Vikas, a daughter of psychiatrists from India, not to train in osteopathic medicine because of its “stigma.” They told her: “Don’t go to a D.O. school, you don’t want to be a second-class citizen.” But she did, inspired after shadowing two D.O. psychiatrists as a high school student. “Now,” she added, underscoring what the statistics make clear, “it is more and more acceptable.”

Dr. Goldberg believes osteopaths have a strong case to make. Too many doctors, he said, rely on expensive medical tests like CT scans and M.R.I.s and fail to probe or even touch the patient’s body. Osteopathic schools, on the other hand, stress physical diagnosis techniques like palpation or percussion — gently tapping the abdominal area, say, to determine if the size and shape of the liver suggest inflammation. An osteopath might more quickly notice that if a pregnant woman’s posture is askew her fetus is imposing a burden on her skeleton.

The D.O. philosophy makes much of patient interaction. “I hate the term holistic, but we look at the patient as a whole — from their biological, psychological, social, occupational and family background,” said Dr. Goldberg, a physiatrist (rehabilitation specialist) by training. “We teach respect for technology and laboratory testing to aid in making a diagnosis, but count on the history and physical examination to confirm it. In that way, we’re old-fashioned.”

Touro also operates osteopathic campuses in Vallejo, Calif., and Henderson, Nev., and it took over New York Medical College, a conventional medical school, three years ago. Many osteopathic schools have been established in rural areas, in keeping with a mission to embed doctors in underserved areas. A 2010 report called “The Social Mission of Medical Education” noted the successful placement of schools in nontraditional locations, citing Pikeville, Ky., and Harlem. But it also found osteopathic schools behind allopathic schools in recruiting underrepresented minorities.

For Harlem, Touro crafted a mission statement that emphasizes the need to increase minorities in the practice of medicine, and doctors in its community. It’s too early to gauge how well it’s faring, as the first graduates are still making their way through residencies. But while Touro has more than double the number of underrepresented minorities than a typical osteopathic school, only 9 percent are Hispanic and 7 percent black.

Last fall, Jemima Akinsanya and fellow minority students were discussing how little they had known about their options for a career in medicine. “We thought it would be great if there were some student-run organization that could reach out and tell other minority students about our experiences,” said Ms. Akinsanya, who was born in Nigeria. With the goal of increasing minority enrollment at Touro, they formed Compass, which stands for Creating Osteopathic Minority Physicians Who Achieve Scholastic Success. Already, the group has held a meet-and-greet at the Apollo and attended college fairs. Ms. Akinsanya accompanied an admission representative to City College, where she says she was inundated with questions. “Osteopathic medicine is still up and coming,” she said. “A lot of people don’t know about D.O.s. Their physician might be one, but they don’t know it.”

An osteopathic school like his, Dr. Goldberg said, looks for students with subtly distinctive virtues. They consider students’ record in humanities subjects as well as “what they’ve done with their lives.” Volunteering for a soup kitchen or medical clinic or excelling as a child of a low-income single mother might make up for a lower M.C.A.T. score. “That somebody was able to perform well as an undergraduate given the need of family and survival told us about those grades and M.C.A.T. scores,” Dr. Goldberg said.

I met students who reflect the kind of student Touro seeks.

Cassandre N. Marseille, a Haitian who moved to New York to study at Stony Brook University, said she Googled “how do you become a physician in the U.S.”

“I’d never heard of a D.O.,” she said. “I looked into it and was impressed and liked the approach. When it came time to apply I just applied to D.O. schools.”

Ms. Marseille would like one day to practice medicine in Haiti but for the immediate future sees herself working in Harlem. “I still have to pay back debt and won’t be able to do it on a Haitian physician’s salary,” she said. “This is $250,000 of taxpayer money I won’t be able to pay back.”

Touro’s current students worry about the debt they are accumulating (tuition and fees at conventional and osteopathic schools are roughly comparable; at Touro, the cost is $45,000 a year) as well as whether there will be a residency for them when they graduate (98 percent of this year’s graduates have been matched).

Aldo Manresa, a second-year student and son of Cuban refugees who were part of the 1980 Mariel boatlift, attended Florida International University as a philosophy major but was drawn to medicine. He wants to be a primary-care physician partly because of the shortage. But as with all the students I met, what appealed to him most was the idea of treating patients with his hands — “instead of sending you for prescription medication.”

Joseph Berger is a New York-based reporter for The Times.