- Joined

- Jul 1, 2018

- Messages

- 17

- Reaction score

- 5

I recently interviewed a MD-PhD professor from a very prestigious institution, he does a pretty typical 80-20 research-clinical split for his career. While he had an impressive academic track record, I can't help but feel like his research wasn't as top-notch as I expected compared to some PhD professors I interviewed in the same department, and his students receive less mentorship because he's always busy. So I am wondering if splitting time between clinics and research makes it harder to really be the best in either field.

For me personally, although I have a genuine interest in practicing medicine as well as research, if I have to choose one, I would go with research. And I want to try to be the best in one thing more than being ok in both things.

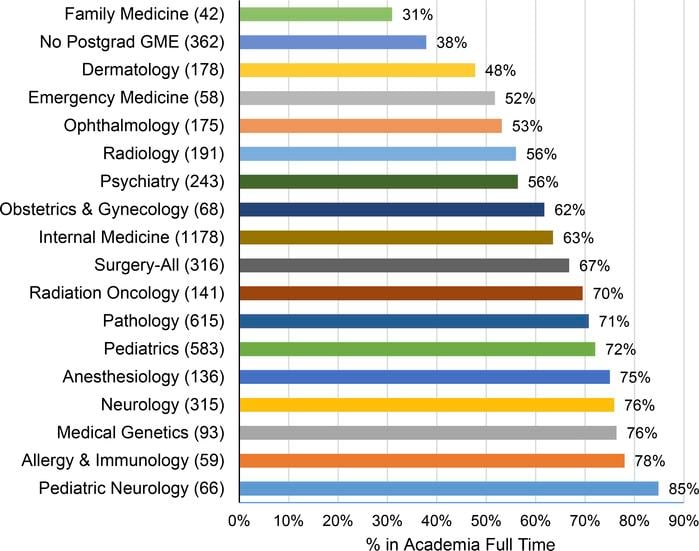

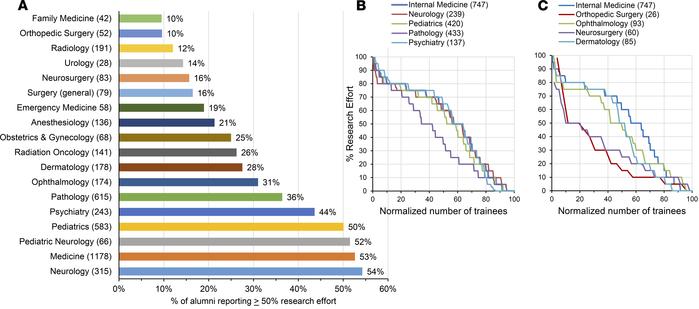

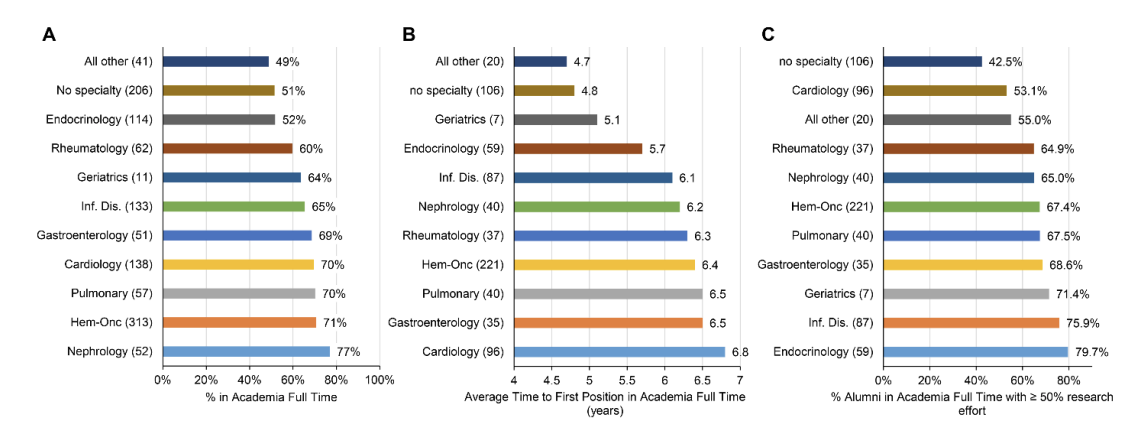

So realistically speaking, I'd like to ask current physician-scientists in this forum, do you feel like your clinical practices and your research are actually synergistic to each other or they are distracting each other. I understand that national surveys say that most MD-PhD graduates go into research, but I am not clear on how good their research is, compared to their PhD counterparts given that most of them will spend less than a full time job in lab.

TL; DR:

1. In a realistic world (with time constraint etc) , is MD and PhD really synergistic or are they distracting each other from becoming the best possible in respective field? Let's say I will follow the traditional 80:20 split and my research field is something very clinically-relevant like cancer (with MD in something related to oncology)

Thank you!

For me personally, although I have a genuine interest in practicing medicine as well as research, if I have to choose one, I would go with research. And I want to try to be the best in one thing more than being ok in both things.

So realistically speaking, I'd like to ask current physician-scientists in this forum, do you feel like your clinical practices and your research are actually synergistic to each other or they are distracting each other. I understand that national surveys say that most MD-PhD graduates go into research, but I am not clear on how good their research is, compared to their PhD counterparts given that most of them will spend less than a full time job in lab.

TL; DR:

1. In a realistic world (with time constraint etc) , is MD and PhD really synergistic or are they distracting each other from becoming the best possible in respective field? Let's say I will follow the traditional 80:20 split and my research field is something very clinically-relevant like cancer (with MD in something related to oncology)

Thank you!