The first significant advance in heart stents in more than a decade is providing U.S. patients and their doctors with a new option for treating blockages in the coronary arteries that cause chest pain and heart attacks.

Last week, cardiologists began implanting

Abbott Laboratories ’ new biodegradable stent called Absorb in patients following

its approval last Tuesday by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Unlike the permanent metal devices that have been used to prop open diseased vessels for more than 20 years, Absorb is designed to fully dissolve within two to three years after it is deployed.

Proponents of the new device believe it holds the potential for long-term benefits over metal stents, including widely used drug-coated stents that have dominated the market since 2003. Some 850,000 patients in the U.S. are treated with stents each year.

“As good as the drug-coated stents have been, there is a downside,” says David Rizik, an interventional cardiologist at HonorHealth Scottsdale Shea Medical Center in Arizona.

ENLARGE

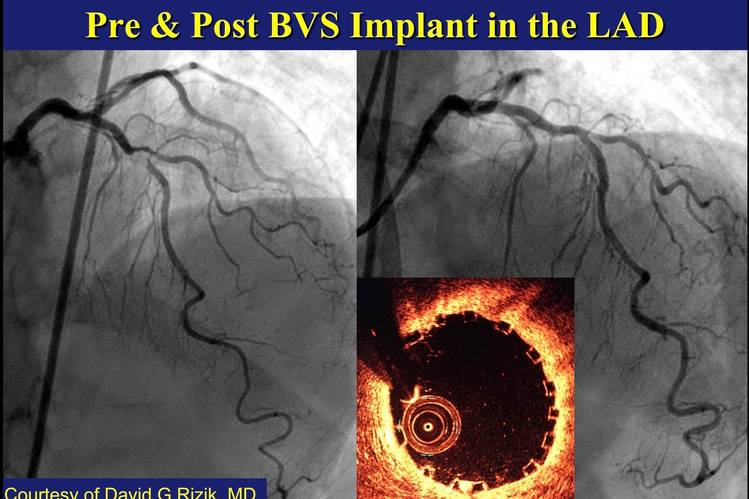

This is a pre- and post-procedure look at Mr. Taylor's stented artery. The inset on the right is an image of the vessel taken from the inside. The little square boxes around the circumference of the artery show that the stent is properly place against the artery wall.Photo: David Rizik, MD/HonorHealth

After the first year, new disease can accumulate in metal devices, with the result that 2% to 3% of patients a year suffer a heart attack or other serious problem related to the treated obstruction. Doctors often put patients on a prolonged blood-thinning regimen to reduce risk of a life-threatening clot. Metal stents can complicate diagnosis and future treatment, including bypass surgery, when symptoms recur as they often do.

The hope is that a dissolving stent will reduce the need for repeat procedures in later years, enable many patients to shorten the time they’re on blood thinners and help restore normal motion to their arteries.

“The promise of the device is three to five years down the road,” Dr. Rizik says. Dr. Rizik is a member of Abbott’s medical advisory board.

The argument made sense for Doug Taylor, a 73-year-old avid runner and owner of a wealth-management firm in Scottsdale, Ariz. He became the first patient in the U.S. to get the new absorbable stent after it won FDA approval when Dr. Rizik performed the procedure on Wednesday.

“I really like the idea that it’s going to dissolve and be out of there,” Mr. Taylor says.

That said, the anticipated long-term benefits of the dissolving device are yet-to-be proven. Results of studies examining the question are due within the next several years. Meantime, some cardiologists are concerned about the absorbable stent’s near-term performance.

ENLARGE

The new biodegradable heart stent from Abbott Laboratories Photo: F. Martin Ramin/The Wall Street Journal

The 2,008-patient clinical trial that led to its approval found that after one year the absorbable device was essentially equivalent in efficacy and safety to Abbott’s drug coated metal stent called Xience, which remains in the body permanently. Actual differences, though not statistically significant, went against the new device: 7.8% of Absorb patients and 6.1% of Xience patients suffered a serious adverse event related to the treated blockage.

In particular, the rate of stent thrombosis—the potentially catastrophic formation of clots in the device—was 1.5% for Absorb compared with 0.7% for Xience. That indicates stent thrombosis affects 15 of every 1,000 Absorb patients versus about 7 people per 1,000 with Xience. Studies in Europe, where the device has been on the market for several years, have revealed a similar trend.

“The concept of self-degrading stents is intuitively attractive,” Robert Byrne, a cardiologist in Munich, Germany, wrote in an editorial last fall in the New England Journal of Medicine. But “promise alone is not enough to make us unconditionally embrace this technology.” Unless their advantages become evident, they won’t be widely accepted, he said.

The main problem, researchers believe, is that absorbable stents are bulkier and less forgiving than the metal ones. That means people with very small arteries, who may be more vulnerable to a clot, and those with very large ones aren’t good candidates for the device. Nor are patients with substantial calcification of the deposits in their arteries or with twisting vessels, doctors say.

That means cardiologists need to take extra care to estimate the size of patients’ vessels before recommending the dissolvable stent and to make sure they implant it completely against the vessel wall. That will likely require sophisticated imaging and other equipment that could increase the cost of the procedure.

“This technology will not achieve its projected benefit if (cardiologists) don’t apply it precisely,” says Marco Costa, an interventional cardiologist at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, and a proponent of the device.

Cost implications haven’t been fully analyzed, doctors say, but any additional upfront costs could be offset by future savings if the costs of repeat procedures and other metal-stent related treatments are reduced. Doctors expect future versions of absorbable stents will solve some of the current limitations.

Mr. Taylor says he carefully weighed the pros and cons before accepting Dr. Rizik’s recommendation that he be treated with the new stent. Since his father died in 1973 at age 63 after having suffered several heart attacks, Mr. Taylor has embarked on a deliberate effort to avoid a similar fate.

ENLARGE

Heart patient Doug Taylor, in green, and his doctor, David Rizik, an interventional cardiologist at HonorHealth Scottsdale Shea Medical Center in Arizona. Photo: HonorHealth

He began running along the Delaware River that year, when he lived in New Jersey. Then he accepted a friend’s invitation to run a 10K race in New York’s Central Park and got hooked. He soon progressed to marathons and then to 50-mile and 100-mile road races.

Recently, he began experiencing chest pain and nausea whenever he ran faster than a 14-minute mile. An initial evaluation didn’t turn up any heart trouble, but the problem persisted.

A few weeks ago, the pain and nausea came even when he wasn’t running. A trip to the emergency room in early June led him to the cardiac catheterization lab where Dr. Rizik discovered a 90% blockage in one artery and an 80% obstruction in another.

He opened the most occluded vessel with a metal stent, and Mr. Taylor’s pain went away. Then Dr. Rizik told him approval of the new stent was imminent and he could be the first patient in the U.S. to get one for the other blockage. That was in his left anterior descending artery, the heart’s most important vessel.

“I’m like, ‘um, it sounds like guinea pig to me,’ ” Mr. Taylor says. But he agreed to consider it and in the end, his running experience was a factor in his decision.

Cardiologists at HonorHealth Scottsdale Shea Medical Center as they implant the absorbable stent in Doug Taylor on Wednesday, July 6. They are looking at an Optical Coherence Tomography imaging screen. Photo: HonorHealth

In marathons and 100-mile races, “you know right from the very beginning that the finish line is a long way away,” he says. “I didn’t want to do something that just gets me over the symptoms of today.”

During last Wednesday’s procedure, Dr. Rizik encountered moderate calcification in the blockage, requiring “meticulous” stretching of the artery with a balloon, he says. The device was successfully placed and imaging with infrared light technology revealed “a wide open vessel,” he says.

Later, Mr. Taylor experienced chest pain that Dr. Rizik told him may have resulted from the stretching. Dr. Rizik performed a second catheterization to check the stent and found everything ok. Overall, “we had a terrific result,” he says.

Back home over the weekend, Mr. Taylor says “things seem to be heading back to normal.” He’s looking forward to Aug. 1, when Dr. Rizik said he could resume running. At some point he’d like to do another marathon.

“I’ve run New York four times,” he says, and “wouldn’t mind” doing it again.