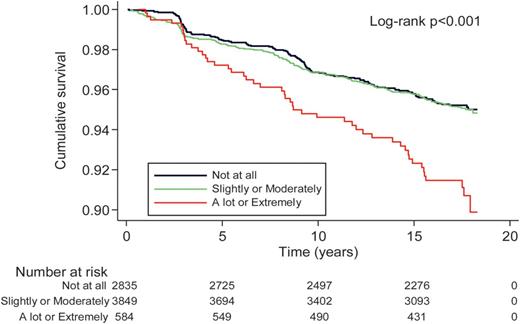

Not arguing with sleep deprivation. Sleep is extremely important. Stress is being overturned, however. How much stress you’re under does not affect health. It’s how you MANAGE it.

No.

Here is an excerpt from a peer reviewed article not some book published by a psychologist.

Heart and stress system

Psychosocial factors as independent risk factors for cardiac diseases

Chronic stressors such as negative psychosocial factors represent modifiable risk factors that could be linked to adverse cardiac prognosis and the mortality rate worldwide. The international INTERHEART case control study proved that psychosocial factors were significantly related to acute myocardial infarction, with an odds ratio (OD) of 2.67 (58).

Social inequalities and behavioral factors as determinants of CV morbidity and mortality were also investigated by M. Marmot and colleagues (

59) in a cohort of British civil servants who worked in the late 1960s (the Whitehall I study) and in 1985–88 (the Whitehall II study). The results from these long-term prospective studies, initially considered platforms for studying age-related diseases, for the first time linked lower socioeconomic status (SES) and lower employment grade with a higher incidence of metabolic syndrome stigmata and a higher coronary mortality rate among male employers. Other combined variables associated with increased risk of CVD mortality were high-strain work (low control and high demands) and low social support. In the same cohort, the presence of financial difficulties in lower employment grades was a risk factor for weight gain and metabolic alterations, in particular in female workers. Findings derived from these large cohort studies clearly show the direct correlation between social conditions and metabolic disturbances, coronary disease onset and the mortality rate (

60).

Further meta-analyses of prospective observational studies found that certain psychosocial factors, such as social isolation and loneliness, were associated with a 50% increased risk of CVD; work-related stress showed similar results, with a 40% risk of new CV events (

61).

Experimental data confirmed that adverse early life events, including social deprivation and discrimination during childhood and adolescence, predispose an individual toward the development of CVD in adulthood through diverse epigenetic signatures of key regulatory genes involved in the stress response, immune function, inflammation and metabolism (

62).

However, the lack of statistical power in recent metanalyses does not allow identification of the type of occupational psychosocial factors that can be considered independent risk factors for major cardiac events (

63).

Emotions and cardiovascular disease

As emerged by large observational studies, people with severe mental diseases (i.e., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder) have an increased risk of developing CHD compared with controls, with pooled hazard ratio of 1.54, according to recent meta-analytic results (

64), showing a consistent increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

In 2014, the American Heart Association pointed out the close relationship between high depressive symptoms and poor prognosis after acute myocardial infarction; in a published scientific statement, depression was elevated as an “independent primary risk factor in patients with acute coronary syndrome” (

65,

66). In fact, the incidence of coronary heart disease was measured at a relative risk of 1.90 in the presence of diagnosed depression (

67,

68).

Racial disparities have been considered in many prospective studies, recognizing race-dependent risk factors for blacks, but not whites, in developing cardiac disease. In the REGARDS study, black individuals with depressive symptoms presented a greater risk of CHD diagnosis or revascularization at follow-up (

69). In the 10 years of follow-up in the Jackson Heart prospective study, the presence of depressive symptoms was positively correlated with the risk of incident stroke. However, coping strategies observed in some individuals of the cohort may mitigate the increased CHD risk associated with depressive symptoms (

70).

Anxiety is commonly diagnosed together with depressive disorder. Therefore, it is not surprising that there are few studies focusing only on anxiety disturbance and the incidence of cardiovascular disease. In a 2010 meta-analysis by Roest and colleagues, a high anxiety score was a recognized risk factor linked to coronaropathy, although the analysis was not adjusted for depression, a common comorbid disease (

71). In a cohort of thousands of young Swedish military men, those who were diagnosed with anxiety were more likely to experience coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction (

72). Seven years of follow-up in Finnish longitudinal study conducted on healthy people reported an association between anxiety and elevated risk of CHD in women only (

73).

The link between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and incident fatal and non-fatal CVD events is well established. Diagnosis of PTSD was found to be an established risk factor for acute coronary events in the general population in multiple prospective cohort studies (

74) and in subgroup population studies involving veterans (

75) and women (

76).

Positive thoughts and emotions, as well as social cohesion, enhance resilience and influence health trajectories in cardiovascular diseases. In the Health and Retirement Study, optimism appeared to protect against incident heart failure after a cardiac event (

77).

Ethnic differences in positive behavioral responses emerged in the Eastern Collaborative Group prospective study, in which the Japanese attitude called “Spirit of Wa,” integrating a sense of community, collaboration and hierarchical social organization, was a protective factor against further cardiac events in Japanese men undergoing coronary angiogram for CAD (

78). Assessment of baseline coping strategies in another cohort of hypertensive middle-aged Japanese subjects without a history of CVD demonstrated that individuals who presented an approach-oriented coping strategy were more likely to have reduced incidence of stroke and CVD mortality, while an avoidance-oriented behavior was associated with higher CVD incidence and mortality (

79).

In western countries, evidence has shown similar results. Adults in the United States without cardiovascular disease who perceived higher neighbourhood social cohesion presented a reduced likelihood of incident myocardial infarction over 4 years (

80).

Stress and neuroendocrine patterns in cardiovascular disease

Stress in mammals is responsible for complex psycho-neuro-immuno-endocrine responses that primarily involves both the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the autonomic nervous system (ANS), first described by the two founders of stress science, Walter Bradford Cannon and Hans Selye, in the 1930s (

81,

82).

Highly conserved in all vertebrates, including humans, the ANS and HPA systems represent the neuronal and hormonal limbs of the stress response, respectively, and provide both short- and long-term changes in behavior, cardiovascular functions, endocrine and metabolic signals, as well as in host defense and immune responses, enabling the individual classically “to fight or flee” and initiate different coping strategies against stressors of different origins, from physical injuries to psychosocial tasks, in order to successfully adaptation (allostasis). The HPA axis, starting from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, secretes corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) that regulates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland. Cortisol is the main active hormone released from the adrenal gland in response to ACTH in humans, exerting negative feedback control on hypothalamic CRF and pituitary ACTH secretion (

83).

As observed in clinical studies with adults and adolescents, altered HPA axis function may have negative effects on the cardiovascular system, leading to atherosclerotic plaque formation, high blood pressure, insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, and central adiposity. Biomolecular studies confirm that these stigmata correlate with elevated inflammatory markers and endothelial activation with a hypercoagulable state and increased risk of thrombotic events (

84).

A growing body of evidence has demonstrated a close relationship between high levels of cortisol and increased risk of ischaemic heart disease and cardiovascular mortality (

85,

86).

Chronic psychological stress is associated with the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, and serum cortisol might be a reference marker for this disease. Huo et al., showed that serum cortisol levels were higher in the patients with atherosclerosis than in healthy controls, and high plasma cortisol concentrations negatively correlated with circulating immuno-regulatory IL-10, promoting plaque destabilization (

87). Chronic job-related stress leads to metabolic syndrome. Workers suffering from burnout showed dysregulation of the sympathetic vagal balance, with reduced parasympathetic activity, predominance of sympathetic activity, and hyporeactivity of the HPA axis, mainly in males (

88).

R

esults from the Whitehall II study showed that male workers with metabolic syndrome at lower job positions had higher levels of norepinephrine, cortisol and serum IL-6 and manifested a higher heart rate at rest and lower heart rate variability (

89).

As a systemic disease, obesity itself contributes to the risk for CVD through elevations in basal levels of cortisol, inflammatory cytokines and hormones such as leptin and insulin. In an exiguous group of obese college-aged males, Caslin and colleagues showed that an acute mental stress task elicited a vigorous stress reaction, with an increase in heart rate and catecholamine release (epinephrine and norepinephrine), increased immune response with inflammatory cytokine synthesis (TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6) and hormonal changes with a significant reduction in leptin concentrations, without a significant increase in serum cortisol at an early post-task observation time point (

90).