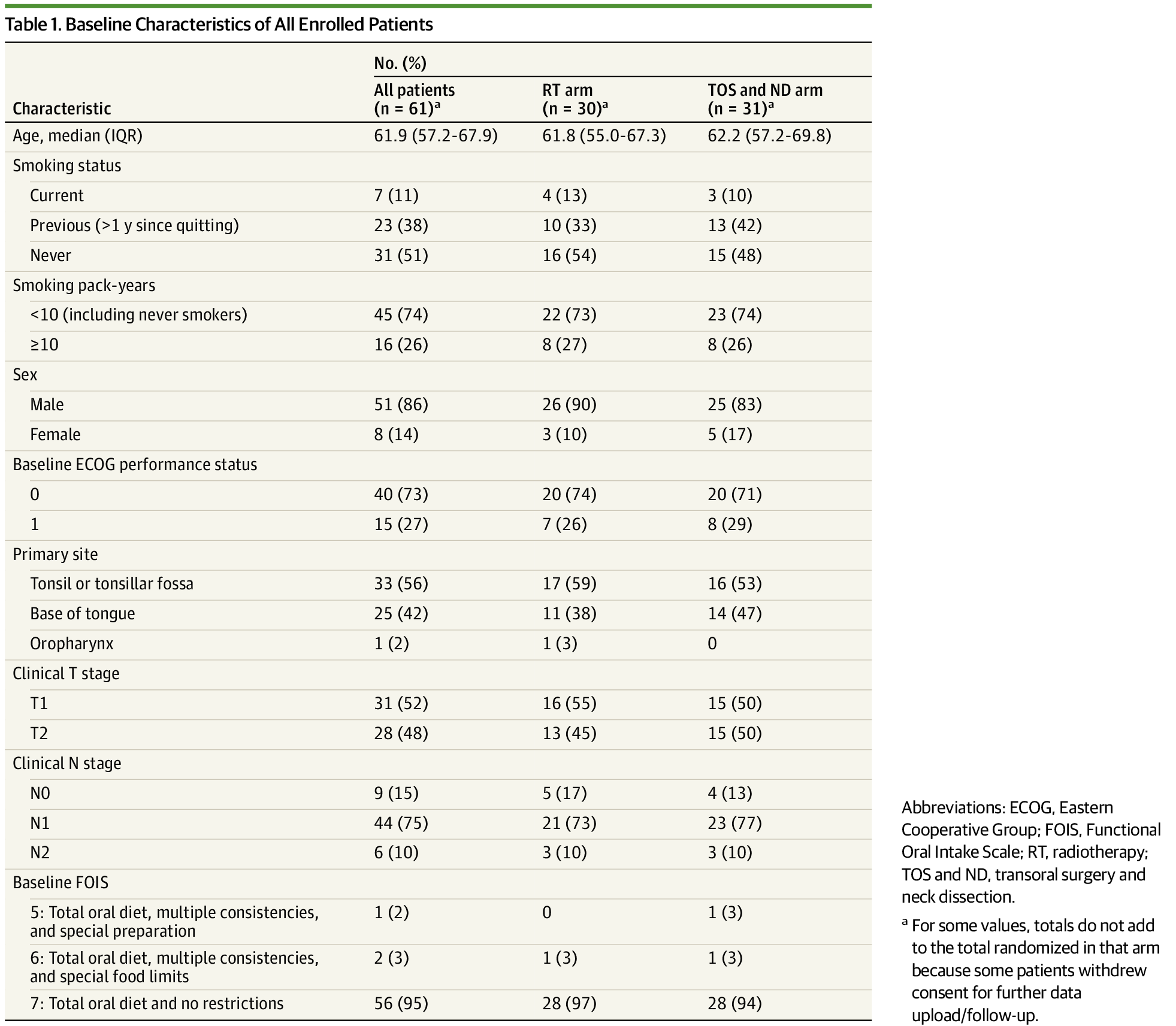

A 61 patient trial (if that's what this is and not some retrospective analysis) that sees a statistically significant difference in outcome is appropriately powered to see the large effect present.

A study's power is determined relative to an

anticipated difference in outcomes.

But even

positive small studies are always dubious (Patchell anyone?). I think this is true even though the p-value...or alpha...or likelihood of committing at Type-1 error isn't supposed to scale with sample size. This is a big part of the failure to replicate phenomenon IMO.

The reason is that random stuff impacts small trials more. When we say that our likelihood of rejecting a true null hypothesis is 0.05, what we are really saying is:

Assuming that these study populations are truly equivalent, the chance that an observed difference based on intervention is due to random variance of outcomes is only 5%.

But even random populations are more and more variant (in a relative sense) the smaller they are! Randomized, small samples are much more likely to not be truly equivalent from a statistical point of view.

ORATOR 2 is a perfect example (I am not pro TORs BTW).

They literally had to close a trial due to an aggregate number of events (whether post-op death or recurrence) on the order of 3-5 total events. Could easily be rando (or real and representative of an infinite number of TORs cases).

Don't do small trials.

(see Riboclib trial in NEJM - statistically signficant improvement, but absolute improvement of < 2%, buoyed by the huge sample size).

Excellent point and the real controversy regarding this trial (not author order). They managed to get ~5000 patients on trial to demonstrate a very small difference in outcomes with a 60% neutropenia rate...this should be discussed more. This may not have even been an ethical trial IMO (will have to think harder about it).

Pharma can game the system this way by having trials that are

too big. It's totally the opposite world of radiation oncology.