I currently usually use a standard 16G needle to draw up propofol (haven't seen those "spikes" since residency) and once in a while I'll see a tiny gray piece of the rubber vial stopper in the drug that I've drawn up. I'll then either try to squirt the piece out or toss the entire syringe. But I wonder how many times I miss some small (or even microsopic) fragments of rubber that are being injected intravenously. Anyone else notice this? What do I do without those spikes that have the filter and what about all the other drugs that we draw up. Is anyone simply popping the tops from all vials first?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Little bits of the propofol stopper

- Thread starter leaverus

- Start date

- Joined

- Jun 23, 2010

- Messages

- 88

- Reaction score

- 106

- Points

- 4,966

- Attending Physician

I believe you are suppose to use a blunt fill needle to draw up, it’s less likely to cut the rubber. It’s just hard to pull up a large amount quickly through it

- Joined

- Apr 24, 2012

- Messages

- 4,943

- Reaction score

- 6,097

- Points

- 6,286

- Resident [Any Field]

Never seen this happen. Only have the 18g blunt tips.

We do use filtered needles when drawing up from glass ampules due to the tiny glass shards that explode out when you pop the top.

We do use filtered needles when drawing up from glass ampules due to the tiny glass shards that explode out when you pop the top.

I currently usually use a standard 16G needle to draw up propofol (haven't seen those "spikes" since residency) and once in a while I'll see a tiny gray piece of the rubber vial stopper in the drug that I've drawn up. I'll then either try to squirt the piece out or toss the entire syringe. But I wonder how many times I miss some small (or even microsopic) fragments of rubber that are being injected intravenously. Anyone else notice this? What do I do without those spikes that have the filter and what about all the other drugs that we draw up. Is anyone simply popping the tops from all vials first?

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2006

- Messages

- 18,575

- Reaction score

- 11,221

- Points

- 6,771

- Location

- Nowhere

- Resident [Any Field]

I've never seen any bit of rubber come up in the syringe. Use a mixture of 18g blunt tips,16g cutting needles depending on institution I'm rotating at. I've accidentally used an 18g blunt tip filter needle to try to pull up propofol...it did not go well.

How big of a rubber piece are we talking about here?

If you're injecting through leurlock ports it shouldn't be a problem right? But through 3 way stop cocks, I suppose you could inject that little piece and have it embolize.

How big of a rubber piece are we talking about here?

If you're injecting through leurlock ports it shouldn't be a problem right? But through 3 way stop cocks, I suppose you could inject that little piece and have it embolize.

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2017

- Messages

- 3,755

- Reaction score

- 4,326

- Points

- 5,551

We use plastic spikes. If I use sharp needle, it make a prefect circle.

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2006

- Messages

- 18,575

- Reaction score

- 11,221

- Points

- 6,771

- Location

- Nowhere

- Resident [Any Field]

Found this from 2008, on a perfunctory google search...Near-Embolization of a Rubber Core from a Propofol Vial : Anesthesia & Analgesia

- Joined

- Jun 23, 2008

- Messages

- 343

- Reaction score

- 340

- Points

- 5,191

- Attending Physician

I’ve seen the little rubber piece in my propofol syringe 3-4 times. I just throw everything away and try again with new vial/syringe/needle. Currently my hospital has the clear plastic blunt tip “needles” and I haven’t seen it with those. I don’t recall ever seeing this with any drug other than propofol.

- Joined

- May 24, 2006

- Messages

- 6,749

- Reaction score

- 6,262

- Points

- 6,551

- Location

- somewhere always warm

- Attending Physician

I was going thru this same exact situation last week. Except from those plastic spikes. I have never seen a 16G needle. Started at a new place and in some places there are no blunts nor regular 18g. And I noticed a little black chunk and got a new syringe with a plastic filter and tried to filter it out instead of wasting the drug. Instead I ended up making a mess and throwing everything out.I currently usually use a standard 16G needle to draw up propofol (haven't seen those "spikes" since residency) and once in a while I'll see a tiny gray piece of the rubber vial stopper in the drug that I've drawn up. I'll then either try to squirt the piece out or toss the entire syringe. But I wonder how many times I miss some small (or even microsopic) fragments of rubber that are being injected intravenously. Anyone else notice this? What do I do without those spikes that have the filter and what about all the other drugs that we draw up. Is anyone simply popping the tops from all vials first?

Haven’t used one of these in years as well and honestly had forgotten about them and the little chunks.

I was wondering the same thing about how much of the stuff I have pushed into people. And what potential damage that would cause.

I feel like those things need filters. Otherwise I am starting to draw up using the 21g needles if no 18g which take more time but probably save from getting chunks.

- Joined

- May 24, 2006

- Messages

- 6,749

- Reaction score

- 6,262

- Points

- 6,551

- Location

- somewhere always warm

- Attending Physician

The only time I have ever noticed it, is when I use plastic spikes. And I think last time I used those before nor was residency.We use plastic spikes. If I use sharp needle, it make a prefect circle.

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

I have seen tiny pieces of rubber from the propofol vial dozens of times in syringes. If you use a 16G or 18G standard needle (non filtered) you are exposing your patients to unnecessary risk in my opinion. I think the plastic blunt tip needles are more likely to result in "coring" of the vial than the metal blunt tip needles.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

Coring and Fragmentation May Occur With Rubber Cap and Blunt Needles

A 45-year-old female was being prepared for induction of general anesthesia for a total thyroidectomy. An induction dose of propofol was drawn through a

www.apsf.org

www.apsf.org

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

I have personally drawn up plenty of propofol using the filtered needles. Even though it is more difficult to draw up the propofol using a filtered needle that is the best approach.

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

J Clin Anesth

. 2014 Mar;26(2):152-4.

doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2013.10.007. Epub 2014 Feb 25.

The Incidence of Coring With Blunt Versus Sharp Needles

Tariq Wani 1, Anupama Wadhwa 2, Joseph D Tobias 3

Affiliations expand

With the advent of safety needles to prevent inadvertent needle sticks in the operating room (OR), a potentially new issue has arisen. These needles may result in coring, or the shaving off of fragments of the rubber stopper, when the needle is pierced through the rubber stopper of the medication vial. These fragments may be left in the vial and then drawn up with the medication and possibly injected into patients. The current study prospectively evaluated the incidence of coring when blunt and sharp needles were used to pierce rubber topped vials. We also evaluated the incidence of coring in empty medication vials with rubber tops. The rubber caps were then pierced with either an18-gauge sharp hypodermic needle or a blunt plastic (safety) needle. Coring occurred in 102 of 250 (40.8%) vials when a blunt needle was used versus 9 of 215 (4.2%) vials with a sharp needle (P < 0.0001). A significant incidence of coring was demonstrated when a blunt plastic safety needle was used. This situation is potentially a patient safety hazard and methods to eliminate this problem are needed

. 2014 Mar;26(2):152-4.

doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2013.10.007. Epub 2014 Feb 25.

The Incidence of Coring With Blunt Versus Sharp Needles

Tariq Wani 1, Anupama Wadhwa 2, Joseph D Tobias 3

Affiliations expand

- PMID: 24582180

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2013.10.007

With the advent of safety needles to prevent inadvertent needle sticks in the operating room (OR), a potentially new issue has arisen. These needles may result in coring, or the shaving off of fragments of the rubber stopper, when the needle is pierced through the rubber stopper of the medication vial. These fragments may be left in the vial and then drawn up with the medication and possibly injected into patients. The current study prospectively evaluated the incidence of coring when blunt and sharp needles were used to pierce rubber topped vials. We also evaluated the incidence of coring in empty medication vials with rubber tops. The rubber caps were then pierced with either an18-gauge sharp hypodermic needle or a blunt plastic (safety) needle. Coring occurred in 102 of 250 (40.8%) vials when a blunt needle was used versus 9 of 215 (4.2%) vials with a sharp needle (P < 0.0001). A significant incidence of coring was demonstrated when a blunt plastic safety needle was used. This situation is potentially a patient safety hazard and methods to eliminate this problem are needed

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

To the Editor:

After one inserts a needle through the stopper of a medication vial, a small piece of the stopper is sometimes sheared off (known as coring) and can be noticed floating on the liquid medication. Because of its small size, personnel are not on the lookout for this, or if visualization is blocked by a label, a matching background, or a colored vial, the coring may go unnoticed. This small foreign body can then be aspirated into a syringe and injected into a patient. For many years, the contamination of parenteral fluids and medications by particulate matter has been recognized as a potential health hazard and has been associated with adverse reactions ranging from clinically occult pulmonary granulomas detected at autopsy to local tissue infarction, pulmonary infarction, and death (1,2). Evidence suggests that particle contaminants may not pose a major threat in intact tissue, but may severely compromise tissue perfusion in patients with prior microvascular compromise of vital organs (e.g., after trauma, major surgery, or sepsis) (1). Finally, there is the potential for neurologic damage should such material pass to the left side of the circulation and occlude a cerebral vessel.

Although steps have been taken by some pharmaceutical companies to reduce the risk of coring, manufacturing and quality control standards vary between companies. Economic pressures leading to the increased use of generic drugs, counterfeit drugs, or drugs purchased over the Internet, particularly in developing countries, may result in medication packaging with an increased risk of coring (1).

Although coring is most likely a low-frequency event, other reports of coring (3,4) as well as patent applications for needles that prevent coring suggest that coring continues to occur and is a problem that has not been completely solved.

There is a longstanding recommended technique of needle insertion into a medication vial that reduces the risk of coring (5,6). The needle should be inserted at a 45–60° angle with the opening of the needle tip facing up (i.e., away from the stopper). A small amount of pressure is applied and the angle is gradually increased as the needle enters the vial. The needle should be at a 90° angle just as the needle bevel passes through the stopper.

Smaller gauge needles may reduce the risk of coring, but may make the cored piece more difficult to see should coring occur (7). Using blunt fill needles may also reduce the risk of coring (and needle stick injuries).

Application of this technique incurs no cost and adds at most a few seconds to the time it takes to draw up medication.

Jonathan V. Roth, MD

Associate Professor of Anesthesiology

Thomas Jefferson School of Medicine

Philadelphia, PA

Department of Anesthesiology

Albert Einstein Medical Center

Philadelphia, PA

[email protected]

REFERENCES

1. Lehr HA, Brunner J, Rangoonwala R, Kirkpatrick CJ. Particulate matter contamination of intravenous antibiotics aggravates loss of functional capillary density in postischemic striated muscle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:514–20.

2. Kirkpatrick CJ, Lehr HA, Otto M, et al. Clinical implications of circulating particulate contamination of parenteral injections: a review. Crit Care Shock 1999;4:166–73.

3. Adachi Y, Takigami J, Watanabe K, Satoh T. A case of coring using a 1% Diprivan vial. Masui 2001;50:635–6.

View full references list

After one inserts a needle through the stopper of a medication vial, a small piece of the stopper is sometimes sheared off (known as coring) and can be noticed floating on the liquid medication. Because of its small size, personnel are not on the lookout for this, or if visualization is blocked by a label, a matching background, or a colored vial, the coring may go unnoticed. This small foreign body can then be aspirated into a syringe and injected into a patient. For many years, the contamination of parenteral fluids and medications by particulate matter has been recognized as a potential health hazard and has been associated with adverse reactions ranging from clinically occult pulmonary granulomas detected at autopsy to local tissue infarction, pulmonary infarction, and death (1,2). Evidence suggests that particle contaminants may not pose a major threat in intact tissue, but may severely compromise tissue perfusion in patients with prior microvascular compromise of vital organs (e.g., after trauma, major surgery, or sepsis) (1). Finally, there is the potential for neurologic damage should such material pass to the left side of the circulation and occlude a cerebral vessel.

Although steps have been taken by some pharmaceutical companies to reduce the risk of coring, manufacturing and quality control standards vary between companies. Economic pressures leading to the increased use of generic drugs, counterfeit drugs, or drugs purchased over the Internet, particularly in developing countries, may result in medication packaging with an increased risk of coring (1).

Although coring is most likely a low-frequency event, other reports of coring (3,4) as well as patent applications for needles that prevent coring suggest that coring continues to occur and is a problem that has not been completely solved.

There is a longstanding recommended technique of needle insertion into a medication vial that reduces the risk of coring (5,6). The needle should be inserted at a 45–60° angle with the opening of the needle tip facing up (i.e., away from the stopper). A small amount of pressure is applied and the angle is gradually increased as the needle enters the vial. The needle should be at a 90° angle just as the needle bevel passes through the stopper.

Smaller gauge needles may reduce the risk of coring, but may make the cored piece more difficult to see should coring occur (7). Using blunt fill needles may also reduce the risk of coring (and needle stick injuries).

Application of this technique incurs no cost and adds at most a few seconds to the time it takes to draw up medication.

Jonathan V. Roth, MD

Associate Professor of Anesthesiology

Thomas Jefferson School of Medicine

Philadelphia, PA

Department of Anesthesiology

Albert Einstein Medical Center

Philadelphia, PA

[email protected]

REFERENCES

1. Lehr HA, Brunner J, Rangoonwala R, Kirkpatrick CJ. Particulate matter contamination of intravenous antibiotics aggravates loss of functional capillary density in postischemic striated muscle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:514–20.

2. Kirkpatrick CJ, Lehr HA, Otto M, et al. Clinical implications of circulating particulate contamination of parenteral injections: a review. Crit Care Shock 1999;4:166–73.

3. Adachi Y, Takigami J, Watanabe K, Satoh T. A case of coring using a 1% Diprivan vial. Masui 2001;50:635–6.

View full references list

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

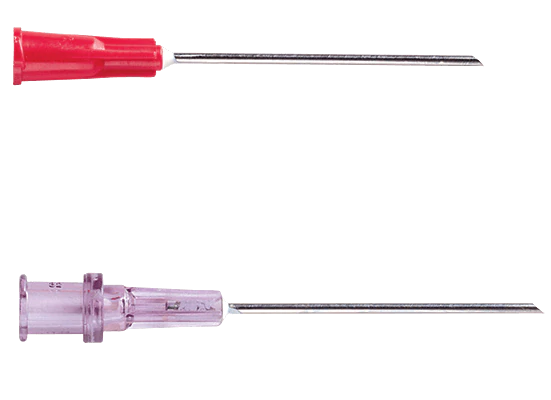

Figure 1:

Figure 1:Comparison of actual vial approaches with the BD™ plastic blunt needle. A, Perpendicular puncture is a 90° approach to the vial. B, Acute angle puncture is an approximately 45° approach to the vial.

The contingency table is presented in Table 1. Coring occurred in 29.2% of the perpendicular puncture group and 15.2% in the angled puncture group (P = 0.0001). There was a 47.8% reduction in coring (95% confidence interval, 26.8%–63.0%) when the angled puncture technique was used. The primary finding is that the frequency of coring with blunt needle impalement of the rubber stopper of Diprivan® vials is reduced with angled puncture compared with perpendicular puncture. By using an angled puncture technique, we achieved an almost 50% reduction in coring.

Table 1:

Table 1:Contingency Table for Propofol Vial Coring with Blunt Fill Needles: Straight Versus Acute Angle Puncture

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

The clinical significance of coring and its microembolic consequences is not well described, likely because it does not have an immediate effect when it is accidentally injected.3,4 Certain manufactures have booklets on “Particulate Contamination” (e.g., Brauna) and describe the ways to prevent intravascular contamination from occurring, which includes the use of in-line IV filters and filter needles for medication aspiration. However, when aspirating propofol, these needles cause slow aspiration as well as the formation of many air bubbles, which can be an inconvenience in a busy practice. The BD™ short plastic blunt fill needle allows for rapid aspiration of propofol with minimal air bubbles, and we nonetheless report a simple technique to reduce the chances of obtaining a core with these blunt needles. It has been suggested that the use of blunt fill needles may reduce the risk of coring (while reducing the incidence of needle-stick injuries)1; however, this current study revealed that coring with the BD™ blunt fill needle still incurred a 29% incidence of coring. Although we only investigated Diprivan® vials, these findings may potentially be expanded to other medication vials. In addition to using this technique to puncture vials, we still recommend that all vials and syringes be inspected rigorously after puncture and aspiration to ensure that no cores can be seen, irrespective of angle of approach of puncture with blunt needles.

Ferrante S. Gragasin, MD, PhD, FRCPC

Z. A. Neethling van den Heever, MB, ChB, DA (SA)

Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine

University of Alberta

journals.lww.com

journals.lww.com

Ferrante S. Gragasin, MD, PhD, FRCPC

Z. A. Neethling van den Heever, MB, ChB, DA (SA)

Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine

University of Alberta

The Incidence of Propofol Vial Coring with Blunt Needle Use ... : Anesthesia & Analgesia

An abstract is unavailable.

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

So, it appears that the use of an 18G or 19G filtered needle is the best approach. But, those needles are slow to draw up propofol and most providers will choose a standard cutting needle or a blunt tip needle. The picture above is instructive in how we should be inserting a non filtered needle into a propofol vial.

- Joined

- May 24, 2006

- Messages

- 6,749

- Reaction score

- 6,262

- Points

- 6,551

- Location

- somewhere always warm

- Attending Physician

Those aren’t every where. Can’t find them at my current hospital. They are my favorite though and I have never seen any chunks with these.

Which of those pics is the right way to draw up? Angled or straight on. I usually do straight on. Guess it’s the wrong way?

thnx for the all the responses so far (and Blade for the usual extensive evidence-based input); unfortunately where I work we don't have access to various types of needles nor the propofol specific spikes, although we do have the blunts (not the kind you smoke). but sometimes, we're talking FAST turnover pain cases and I don't always have time to draw up propofol through the slow blunt needles. I wonder if for these cases, it would be best to simply pop the top off altogether with one of those vial wrenches like we had in residency? and I, too, have only ever noticed fragments in propofol but it must happen for every medication we draw up.

- Joined

- Dec 15, 2005

- Messages

- 17,332

- Reaction score

- 27,233

- Points

- 8,756

- Location

- Home again

- Attending Physician

OK, at the risk of being "that guy" ...

There are all of these reports of bits of stopper getting cored and maybe even getting injected into patients. Some very earnest people have held off perishing for a while by publishing these reports and analyses and letters. Neat.

Obviously injecting rubber chunks into a patient is not desirable. But has there ever been a case where a patient has had documented harm from this? Lungs are pretty good filters. Synthetic rubber is pretty inert. Is anyone actually being harmed?

There are all of these reports of bits of stopper getting cored and maybe even getting injected into patients. Some very earnest people have held off perishing for a while by publishing these reports and analyses and letters. Neat.

Obviously injecting rubber chunks into a patient is not desirable. But has there ever been a case where a patient has had documented harm from this? Lungs are pretty good filters. Synthetic rubber is pretty inert. Is anyone actually being harmed?

- Joined

- May 24, 2006

- Messages

- 6,749

- Reaction score

- 6,262

- Points

- 6,551

- Location

- somewhere always warm

- Attending Physician

Very realistic question. I haven’t looked it up, but since noticing it now, I think I will.OK, at the risk of being "that guy" ...

There are all of these reports of bits of stopper getting cored and maybe even getting injected into patients. Some very earnest people have held off perishing for a while by publishing these reports and analyses and letters. Neat.

Obviously injecting rubber chunks into a patient is not desirable. But has there ever been a case where a patient has had documented harm from this? Lungs are pretty good filters. Synthetic rubber is pretty inert. Is anyone actually being harmed?

- Joined

- May 24, 2006

- Messages

- 6,749

- Reaction score

- 6,262

- Points

- 6,551

- Location

- somewhere always warm

- Attending Physician

Seriously? You are in that much of a hurry that you can’t spare a couple of seconds?thnx for the all the responses so far (and Blade for the usual extensive evidence-based input); unfortunately where I work we don't have access to various types of needles nor the propofol specific spikes, although we do have the blunts (not the kind you smoke). but sometimes, we're talking FAST turnover pain cases and I don't always have time to draw up propofol through the slow blunt needles. I wonder if for these cases, it would be best to simply pop the top off altogether with one of those vial wrenches like we had in residency? and I, too, have only ever noticed fragments in propofol but it must happen for every medication we draw up.

I can’t imagine the 18G drawing up at a significantly slower rate than the plastic tips or the 16G.

Have you timed it?

One thing I hate about the OR lifestyle is the pressure to turn over quickly. Crap happens when we are rushing through cases. Sometimes I miss stuff and wish I had more time. We aren’t taking care of cattle here.

- Joined

- Dec 15, 2005

- Messages

- 17,332

- Reaction score

- 27,233

- Points

- 8,756

- Location

- Home again

- Attending Physician

Also. Doesn't everybody take a syringe with air in it, puncture the vial, push the air in, suck the juice out? If the needle cores the rubber, it gets forced into the bottle. Then it expands a little bit, since it's no longer surrounded by the rest of the stopper under some tension/compression. I wouldn't think it could get sucked out now that it's bigger than the bore of the needle.

It's slow enough getting propofol out of a bottle through an unobstructed 18 g or a filter needle. How is any going to get through the needle with a bore-sized chunk of rubber in the needle?

Has anyone who's ever spotted a floatie in the vial tried to suck it out with the needle that made it? Or did the ensuing panic halt further experimentation?

It's slow enough getting propofol out of a bottle through an unobstructed 18 g or a filter needle. How is any going to get through the needle with a bore-sized chunk of rubber in the needle?

Has anyone who's ever spotted a floatie in the vial tried to suck it out with the needle that made it? Or did the ensuing panic halt further experimentation?

D

deleted875186

I have seen the core make it into my syringe on several occasions.Also. Doesn't everybody take a syringe with air in it, puncture the vial, push the air in, suck the juice out? If the needle cores the rubber, it gets forced into the bottle. Then it expands a little bit, since it's no longer surrounded by the rest of the stopper under some tension/compression. I wouldn't think it could get sucked out now that it's bigger than the bore of the needle.

It's slow enough getting propofol out of a bottle through an unobstructed 18 g or a filter needle. How is any going to get through the needle with a bore-sized chunk of rubber in the needle?

Has anyone who's ever spotted a floatie in the vial tried to suck it out with the needle that made it? Or did the ensuing panic halt further experimentation?

D

deleted875186

What if we simply put an air filter by the patient on all our IV infusions.

boom, solved

boom, solved

D

deleted162650

Isn’t the bigger concern not that the little bit of stopper will embolize, but that now you have contaminated that entire vile and it’s no longer sterile?

- Joined

- May 24, 2006

- Messages

- 6,749

- Reaction score

- 6,262

- Points

- 6,551

- Location

- somewhere always warm

- Attending Physician

Ensuing panic. This made me laugh out loud.Also. Doesn't everybody take a syringe with air in it, puncture the vial, push the air in, suck the juice out? If the needle cores the rubber, it gets forced into the bottle. Then it expands a little bit, since it's no longer surrounded by the rest of the stopper under some tension/compression. I wouldn't think it could get sucked out now that it's bigger than the bore of the needle.

It's slow enough getting propofol out of a bottle through an unobstructed 18 g or a filter needle. How is any going to get through the needle with a bore-sized chunk of rubber in the needle?

Has anyone who's ever spotted a floatie in the vial tried to suck it out with the needle that made it? Or did the ensuing panic halt further experimentation?

I tried sucking it out with the plastic filter thing like the one that comes in a spinal/epidural kit but it was too big for the luer lock.

So flipped it over, took out the plunger, then tried to suction the propofol out from the back end, but it started dripping from the front end into the needle and cap and just made a bit of a mess. I then just ended up suctioning the contaminated solution, adding a little saline to it and put it in the waste container because it is a controlled substance in the hospital system I am currently working in.

I try not to use the plastic tip if there’s an 18g available. Some place only have the long 21G needles which take forever to suction out though.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Dec 2, 2008

- Messages

- 1,010

- Reaction score

- 824

- Points

- 6,111

- Non-Student

First time I ever saw this was when we had the blunt metal needles 'given' to us. In my region there was a spate of this occuring. We incidentally changed supplier of our generic propofol and it stopped.I have seen tiny pieces of rubber from the propofol vial dozens of times in syringes. If you use a 16G or 18G standard needle (non filtered) you are exposing your patients to unnecessary risk in my opinion. I think the plastic blunt tip needles are more likely to result in "coring" of the vial than the metal blunt tip needles.

- Joined

- Dec 2, 2008

- Messages

- 1,010

- Reaction score

- 824

- Points

- 6,111

- Non-Student

Ever tried to push/infuse propofol thru an air filter?What if we simply put an air filter by the patient on all our IV infusions.

boom, solved

D

deleted162650

because it is a controlled substance.

No it isn’t.

Arch Guillotti

Senior Member

Staff member

Administrator

Volunteer Staff

Lifetime Donor

20+ Year Member

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2001

- Messages

- 9,978

- Reaction score

- 7,457

- Points

- 6,606

- Attending Physician

It is if the hospital pharmacy says it is.No it isn’t.

- Joined

- Dec 2, 2008

- Messages

- 1,010

- Reaction score

- 824

- Points

- 6,111

- Non-Student

No it isn't. If what you mean by controlled is requiring counts and documentation of waste and tracking. There isn't a pharmacy in their right mind that would take that on for propofol.It is if the hospital pharmacy says it is.

cthrowaway

Full Member

- Joined

- Apr 26, 2020

- Messages

- 14

- Reaction score

- 65

- Points

- 0

- Attending Physician

No it isn't. If what you mean by controlled is requiring counts and documentation of waste and tracking. There isn't a pharmacy in their right mind that would take that on for propofol.

Many HCA hospitals treat propofol as a controlled substance, and require documentation for every cc. But, your comment remains correct. The pharmacy isn't it its right mind to allow business suits to enforce such a ridiculous policy.

- Joined

- Jul 11, 2001

- Messages

- 3,019

- Reaction score

- 2,034

- Points

- 5,391

- Location

- SF, CA

- Attending Physician

Don’t both they ASA and AANA promote the “one vial, one syringe, one patient” practice? Shouldn’t matter if the vial is no longer sterile because it should be discarded.Isn’t the bigger concern not that the little bit of stopper will embolize, but that now you have contaminated that entire vile and it’s no longer sterile?

D

deleted162650

Don’t both they ASA and AANA promote the “one vial, one syringe, one patient” practice? Shouldn’t matter if the vial is no longer sterile because it should be discarded.

Im saying that the top of the vial is not sterile. When it floats around in the prop, you now have potential bacterial contamination of the whole vial.

- Joined

- May 24, 2006

- Messages

- 6,749

- Reaction score

- 6,262

- Points

- 6,551

- Location

- somewhere always warm

- Attending Physician

I love how people live in their own bubbles and then want to argue about stuff that they haven’t ever seen, know nothing about, as if it doesn’t exist.No it isn't. If what you mean by controlled is requiring counts and documentation of waste and tracking. There isn't a pharmacy in their right mind that would take that on for propofol.

Have you been to every hospital pharmacy in America? In your state? Even your city?

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 123

- Reaction score

- 196

- Points

- 4,741

- Attending Physician

Good question about the rubber contaminating the entire vial. You would think this would have been answered many times already by some resident desperate for a pub. As far as I know it hasn't. I can say I asked the same question of an infectious disease guy some 25 years ago. His answer, "Probably not". My guess is that routine bacteremia from simple stuff like brushing teeth is a more common source. The again, if you don't brush your teeth....

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2017

- Messages

- 3,755

- Reaction score

- 4,326

- Points

- 5,551

Good question about the rubber contaminating the entire vial. You would think this would have been answered many times already by some resident desperate for a pub. As far as I know it hasn't. I can say I asked the same question of an infectious disease guy some 25 years ago. His answer, "Probably not". My guess is that routine bacteremia from simple stuff like brushing teeth is a more common source. The again, if you don't brush your teeth....

Why would it be non sterile? If you drew everything into a 20cc syringe? Unless you assume right after cap is off the vial, it becomes unsterile.

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

A cored piece of propofol rubber cap after the cap was pierced with a blunt tip plastic needle to draw the medication. Such contamination has been linkedto latex sensitivity and fragment embolization.

A 45-year-old female was being prepared for induction of general anesthesia for a total thyroidectomy. An induction dose of propofol was drawn through a disposable syringe attached to a blunt plastic needle to pierce the rubber stopper. After the needle was withdrawn, a dark object was seen at the bottom of the propofol vial. Upon close inspection, a cored piece of rubber from the vial’s rubber stopper was identified (Figure).

The issue of coring, the shearing off of a portion of the rubber stopper from a medication vial as it is pierced has been described in the past. The frequency of such incidents seems to be rising as the use of blunt plastic tips increases. Per one study, the incidence of coring was 29% with blunt plastic needles as opposed to only 4% with acutely beveled sharp steel needles.1 The cored fragments can be difficult to visualize because of their small size, the masking effect of the vial labels, or the medication opacity.

Exposure to the macro and microscopic rubber fragments has been linked to latex allergy as well as embolization into small vessels causing ischemia.2 Aspiration of a cylinder shaped rubber core back into the syringe followed by introduction into a patient’s blood stream might seem an unlikely combination of events. A case of near-embolization of the rubber core from a propofol vial that lodged itself into the 24-gauge angiocath interrupting the propofol infusion and setting off the high-pressure pump alarm during a rigid bronchoscopy has been reported.3

Microscopic rubber particles can contaminate the medication and upon systemic administration may cause latex allergy. Isolated cases of systemic reactions to latex allergens have been reported and often associated with the use of multidose vials.4

The amount of latex protein in the multidose vials was determined to be extremely low in 1 study after the rubber stopper was punctured 40 times.5 As we try to protect personnel and patients from the dangers of needle sticks, we may be increasing exposure of our patients to unintended risks.

he use of blunt needles with filters may prevent aspiration of the macro rubber particles. Removing the rubber stopper from the vial altogether addresses the macro or microscopic particle contamination concerns but may increase the potential for errors in dosage, dilution, contamination, and waste.6 Each health care institution should therefore formulate management guidelines for the use of multidose vials in the care of latex-sensitive patients.

Tariq Chaudhry, MD

Andrew Serdiuk, DO

Moffitt Cancer Center

Tampa, Florida

References

- Wani T, Govinda R, Wadhwa A. Studying incidence of coring in anesthesia practice and difference between blunt and sharp needles. [abstract] Anesthesiology 2008;109:A368.

- Sakai O, Furuse M, Nakashima N. Cut-off fragments of rubber caps of bottles of contrast material: Foreign bodies in the drip infusion system. Am J Neuroradiol 1996;17:1194-5.

- Riess ML, Strong T. Near-embolization of a rubber core from a propofol vial. Anesth Analg2008;106:1020-1.

- Vassallo SA, Thurston TA, Kim SH, Todres ID. Allergic reaction to latex from stopper of a medication vial. Anesth Analg 1995;80:1057-8.

- Yunginger JW, Jones RT, Kelso JM, Warner MA, Hunt LW, Reed CE. Latex allergen contents of medical and consumer rubber products. [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol 1993;91:241.

- Senst BL, Johnson RA. Latex allergy. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1997;54:1071-5.

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

Honestly, I’ve seen small bits of cored rubber in propofol syringes dozens of times. If I see it I either toss the syringe or I get another new syringe with a filtered needle and suck out the propofol. I refuse to inject any propofl with a piece of rubber in the syringe.

The correct way to insert any needle is at a 45 degree angle into the vial. This will reduce coring by 50 percent.

Does anyone use a particular type of tool to pull off the tops of the propofol vials? If you have a particular tool that works well please post a picture or link.

For now my plan is to insert all needles at a 45 degree angle into the vial.

The correct way to insert any needle is at a 45 degree angle into the vial. This will reduce coring by 50 percent.

Does anyone use a particular type of tool to pull off the tops of the propofol vials? If you have a particular tool that works well please post a picture or link.

For now my plan is to insert all needles at a 45 degree angle into the vial.

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

FWIW, the study linked below recommends the red blunt tipped needles inserted at a 45 degree angle into the vial.

Clinical risks induced by intravenous administration of visible particulate matter are still incompletely characterised or documented, yet macroscopic particles have been incriminated as being able to cause phlebitis and venous inflammatory reactions [9], reduce tissue capillary perfusion [10], induce the formation of pulmonary embolisms, injection site reactions and granuloma [11], and have even been implicated in a deadly small bowel infarction [12].

The administration safety of injectable drugs is ensured notably by the absence of visible particles in the injected preparation. Regulatory texts worldwide concerning visible particle indicate that parenteral preparations are essentially free from visible particulates [13], clear and practically free from particles [14], or clear and free from readily detectable foreign insoluble matters [15]. However, direct intravenous injections, such as with propofol, remain at risk, as the medication withdrawn from the vial is directly administered to the patient.

www.degruyter.com

www.degruyter.com

Clinical risks induced by intravenous administration of visible particulate matter are still incompletely characterised or documented, yet macroscopic particles have been incriminated as being able to cause phlebitis and venous inflammatory reactions [9], reduce tissue capillary perfusion [10], induce the formation of pulmonary embolisms, injection site reactions and granuloma [11], and have even been implicated in a deadly small bowel infarction [12].

The administration safety of injectable drugs is ensured notably by the absence of visible particles in the injected preparation. Regulatory texts worldwide concerning visible particle indicate that parenteral preparations are essentially free from visible particulates [13], clear and practically free from particles [14], or clear and free from readily detectable foreign insoluble matters [15]. However, direct intravenous injections, such as with propofol, remain at risk, as the medication withdrawn from the vial is directly administered to the patient.

Rubber Coring of Injectable Medication Vial Stoppers: An Evaluation of Causal Factors

Purpose: Coring of a medication vial’s rubber stopper has been reported as a major cause of visible particle presence in injectable preparations. In this study, we investigated and quantified visible particle formation caused by coring associated with four potential causal factors. Methods: The...

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

Here is the conclusion from that study I mentioned previously:

In conclusion to this work, we have shown that rubber coring can be partially reduced by the use of an adapted puncture technique, and totally eliminated by using blunt metal needles.

In conclusion to this work, we have shown that rubber coring can be partially reduced by the use of an adapted puncture technique, and totally eliminated by using blunt metal needles.

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2007

- Messages

- 22,840

- Reaction score

- 9,893

- Points

- 9,821

- Location

- Southeast

- Attending Physician

These needles are the ones I typically use to draw up propofol. I’ll start inserting the needle at a 45 degree angle as well. So far, I have not seen any coring with these needles but I’m willing to bet at least a few of you have seen coring issues.

- Joined

- May 24, 2006

- Messages

- 6,749

- Reaction score

- 6,262

- Points

- 6,551

- Location

- somewhere always warm

- Attending Physician

The top of the vial is supposedly non sterile. At least I have heard that multiple times.Why would it be non sterile? If you drew everything into a 20cc syringe? Unless you assume right after cap is off the vial, it becomes unsterile.

Can’t say I have looked him up.

D

deleted162650

Why would it be non sterile? If you drew everything into a 20cc syringe? Unless you assume right after cap is off the vial, it becomes unsterile.

The plastic cap is just a dust cover. The top of the vial is not - and wasn’t ever - sterile.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 14

- Views

- 2K