- Joined

- Apr 26, 2004

- Messages

- 109

- Reaction score

- 45

Medical misadventures in opioid prescribing...

‘Unintended Consequences’: Inside the fallout of America’s crackdown on opioids

‘UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES’

Inside the fallout of America’s crackdown on opioids

By Terrence McCoy, Photos by Bonnie Jo Mount

May 31, 2018

Comments

COLVILLE, Wash. —

The morning of the long drive, a drive he took every month now, Kenyon Stewart rose from the living room recliner and winced in pain. He looked outside, at the valley stretching below his trailer, and again wondered whether it was getting time to end it. He believed living was a choice, and this was how he considered making his: a trip to the gun store. A purchase of a Glock 9mm. An answer to a problem that didn’t seem to have one.

Stewart is 49 years old. He has long silver hair and an eighth-grade education. For the past four years, he has taken large amounts of prescription opioids, ever since a surgery to replace his left hip, ruined by decades of trucking, left him with nerve damage. In the time since, his life buckled. First he lost his job. Then his house, forcing a move across the state to this trailer park. Then began a monthly drive of 367 miles, back to his old pain clinic, for an opioid prescription that no doctor nearby would write.

“It’s 10 after,” reminded Tyra Mauch, his partner of 27 years, watching him limp over to her.

“Got to go,” he said, nodding.

He hugged her for a long moment, outside the bathroom with the missing door, head full of anxiety. He knew what awaited him on the other side of the drive. Another impossibly difficult conversation with his provider, who, scared by the rising number of opioid prescribers facing criminal prosecution, would soon close the pain clinic. Another cut in his dosage in preparation for that day. More thoughts of the Glock.

The story of prescription opioids in America today is not only one of addiction, overdoses and the crimes they have wrought, but also the story of pain patients like Kenyon Stewart and their increasingly desperate struggles to secure the medication. After decades of explosive growth, the annual volume of prescription opioids shrank 29 percent between 2011 and 2017, even as the number of overdose deaths has climbed ever higher, according to the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science, which collects data for federal agencies. The drop in prescriptions has been greater still for patients receiving high doses, most of whom have chronic pain.

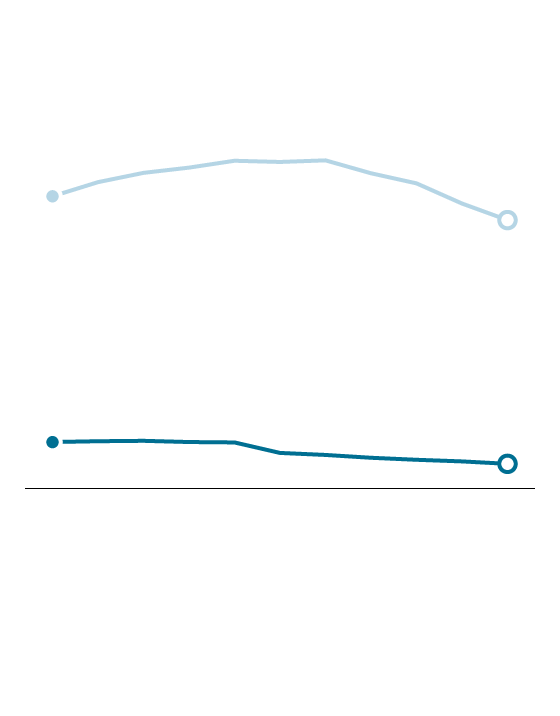

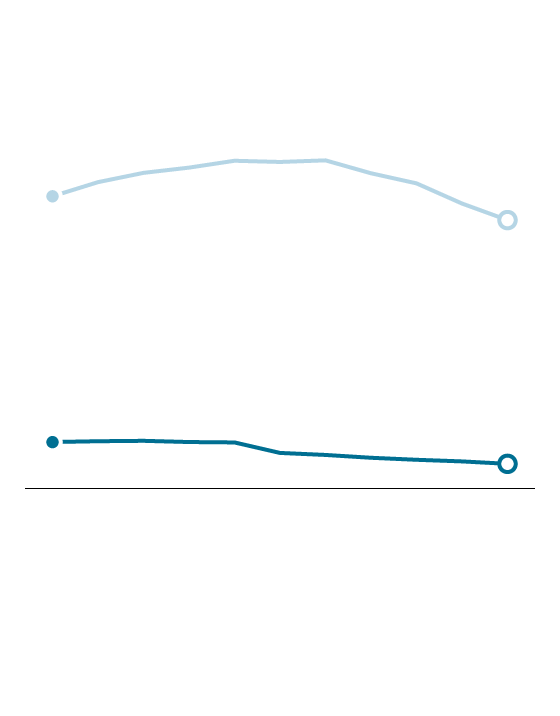

Opioid dosages at a 10-year low

Prescriptions per 100 people

All dosages

72.4

66.5

11.5

High dosage

6.1

2006

2016

Source: QuintilesIMS Transactional Data Warehouse, Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention

THE WASHINGTON POST

The correction has been so rapid, and so excruciating for some patients, that a growing number of doctors, health experts and patient advocates are expressing alarm that the race to end one crisis may be inadvertently creating another.

“I am seeing many people who are being harmed by these sometimes draconian actions amid this headstrong rush into finding a simple solution to this incredibly complicated problem,” said Sean Mackey, the chief of Stanford University’s Division of Pain Medicine. “I do worry about the unintended consequences.”

Chronic pain patients, such as Stewart, are driving extraordinary distances to find or continue seeing doctors. They are flying across the country to fill prescriptions. Some have turned to unregulated alternatives such as kratom, which the Drug Enforcement Administration warns could cause dependence and psychotic symptoms. And yet others are threatening suicide on social media, and have even followed through, as doctors taper pain medication in a massive undertaking that Stefan Kertesz, a professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who studies addiction and opioids, described as “having no precedent in the history of medicine.”

The trend accelerated last year, in part as a result of guidelines the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published in 2016. Noting that long-term opioid use among patients with chronic pain increased the likelihood of addiction and overdose, and had uncertain benefits, they discouraged doses higher than the equivalent of 90 milligrams of morphine.

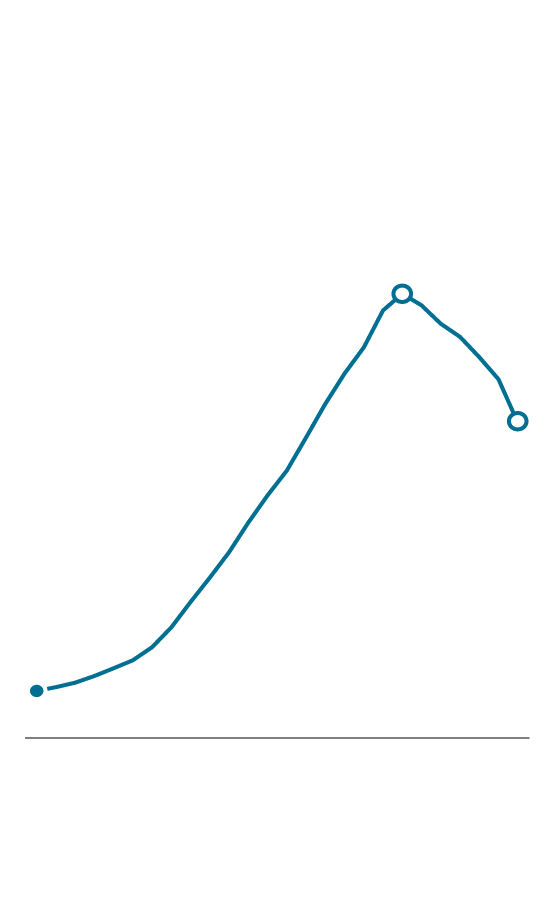

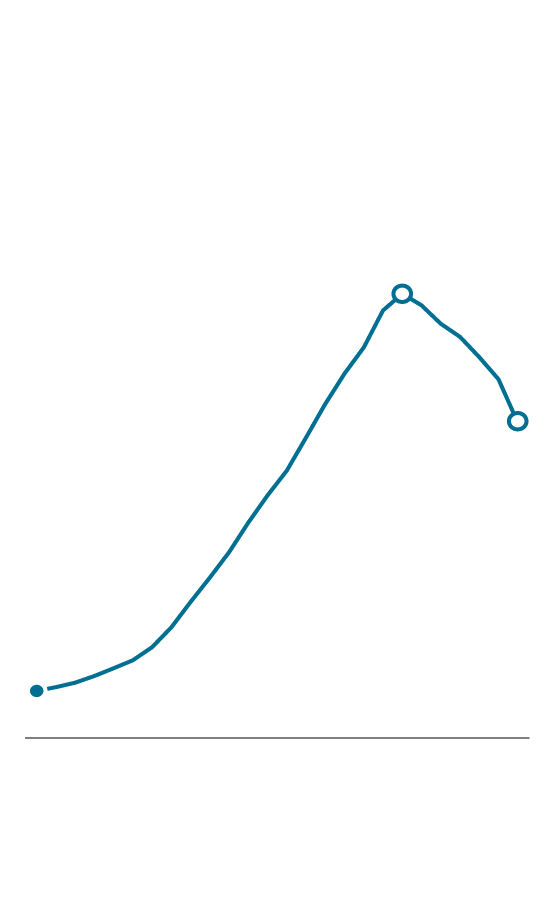

The rise and fall of opioid prescriptions in the U.S. since 1992

Prescribed morphine milligram equivalents, in billions

240.3

170.7

25.4

1992

2011

2017

Source: IQVIA Institute for Human

Data Science

THE WASHINGTON POST

The guidelines, criticized as neither accounting for the differences in how quickly patients metabolize opioids nor addressing clearly enough what to do about patients who were receiving more than 90 morphine milligrams, helped open a new era of regulation. Dozens of states, Medicare and large pharmacy chains such as CVS have since announced or imposed restrictions on opioid prescriptions. The Justice Department, in a continuing push to crack down on pill mills and reckless doctors, announced in January that it would focus on providers writing “unusual or disproportionate” prescriptions. And some physicians, fearful of the financial and legal peril in prescribing opioids, and newly aware of their hazards, have stopped prescribing them altogether.

“We have to be careful of using a blunt instrument where a fine scalpel is needed,” said former surgeon general Vivek H. Murthy, who prioritized the opioid crisis during his tenure, and wants to increase access to alternative treatments. “We already experienced a pendulum swing in one direction, and if we swing the pendulum in the other direction, we will hurt people.”

Stewart, who said he hurt more every day, let go of Tyra. “See you Friday night,” he whispered to her. “Like always.”

He went outside to his truck. He checked for the third time that his near-empty pain medication bottles were in his duffle bag. Zipping the bag, he sighed. What he had left — five pills — would never last him until his next refill, two days from now. The pain, the withdrawal: All of it was only hours away. It would hit during the drive. He knew it.

How much longer could he keep doing this? How much longer could he afford to blow $900 a month — on gas, food, two nights in a motel, and pills for which he had no insurance? How much longer could he drive so many miles for less and less?

Something had to change.

But for now he started the truck, pulled out onto the mountain road, and then one mile was down, and there were 366 to go.

have shown they’re twice as likely to commit suicide, and what little research has been done on forcibly tapering opioid regimens has been troubling. One study, published last year in the journal General Hospital Psychiatry, tracked 509 military veterans involuntarily taken off opioids. It reported that 12 percent had suicidal ideation or violent suicidal behavior, nearly three times the rate of veterans at large.

She also knew about the hysteria in online chronic-pain forums. People were threatening to kill themselves because they couldn’t get medication. News articles about pain patients who had done it were being passed around on the Internet. “My wife committed suicide in October as a direct result of this,” said Wes Haddix, a retired dentist in Charlottesville. One doctor, Thomas Kline of Raleigh, N.C., recently came out of retirement and is reaching out to suicidal pain patients. “They write me, ‘Help me, I’m going to kill myself. What can I do?’ ” he said, echoing conversations that were ongoing in Wedvik’s office, too.

Some discussed it overtly: “I’ll be here for six months,” one man had said, “and then I’ll commit suicide.”

Others subtly: “I don’t want to kill myself,” said Karla Friend, a slight woman of 54 years. “But . . .”

Then there were patients such as Kenyon Stewart. Wedvik didn’t know about the Glock. But when he came into her office later that day, and was looking at her from across the desk, eyes red, hair disheveled, leg shaking, she knew something was very wrong.

“Can we have a talk?” Stewart said.

finding a doctor guilty of five federal drug charges, including conspiring to possess and distribute prescription opioids.

In Pennsylvania, the governor was absorbing criticism that he wasn’t combating the opioid crisis after he vetoed a bill that would have regulated drug prescriptions for injured workers.

In Montana, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions was telling an audience in Billings that doctors prescribed too many opioids, and that “we’re going to target those doctors.”

And meanwhile, in Washington state, on the side of a mountain 48 miles south of the Canadian border, Stewart was putting two bottles stuffed with opioids into his pocket and heading into his trailer.

“I missed you,” he said, hugging Tyra. “I missed you so much this time.”

He let her go and went into his bedroom, overrun with things that fit in their old house but not here. He reached up into the closet and placed the pills in an alcove at the top of his closet, where he thought nobody would think to look. He changed into shorts, grunting in pain, then went outside to look at the trailers along the dirt road.

Tomorrow, he would wake early and divide his medication, placing the week’s tapered ration into a plastic baggie. He would get on the computer and unsuccessfully try to buy kratom, which Wedvik had recommended. He would consider the Glock, then push the thought out of his head. “It’s going to be hard,” he would tell Tyra of what awaited, and she would respond, “We’ve been through worse.”

But in this moment, he kept looking out into the valley, the mountain casting a long shadow across half of it.

An elderly neighbor came out and saw him.

“Did you just get back?” she asked, and he nodded.

“Got to go back again?” she asked.

“No more,” he said, turning to head back inside. “I’m done.”

He limped for the stairs and closed the door behind him, as the shadow outside began to move across the rest of the valley.

‘I don’t know how you got this way:’ A young neo-Nazi reveals himself to his family

After the 2016 election, Kam Musser went from supporting white supremacists to joining a neo-Nazi group. And now his mother and grandmother wonder whether they can get him back.

Some say people on disability just need to get back to work. It's not that easy.

Lisa Daunhauer wanted to be one of the few to get off benefits. But first she had to succeed at Walmart.

‘Unintended Consequences’: Inside the fallout of America’s crackdown on opioids

‘UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES’

Inside the fallout of America’s crackdown on opioids

By Terrence McCoy, Photos by Bonnie Jo Mount

May 31, 2018

Comments

COLVILLE, Wash. —

The morning of the long drive, a drive he took every month now, Kenyon Stewart rose from the living room recliner and winced in pain. He looked outside, at the valley stretching below his trailer, and again wondered whether it was getting time to end it. He believed living was a choice, and this was how he considered making his: a trip to the gun store. A purchase of a Glock 9mm. An answer to a problem that didn’t seem to have one.

Stewart is 49 years old. He has long silver hair and an eighth-grade education. For the past four years, he has taken large amounts of prescription opioids, ever since a surgery to replace his left hip, ruined by decades of trucking, left him with nerve damage. In the time since, his life buckled. First he lost his job. Then his house, forcing a move across the state to this trailer park. Then began a monthly drive of 367 miles, back to his old pain clinic, for an opioid prescription that no doctor nearby would write.

“It’s 10 after,” reminded Tyra Mauch, his partner of 27 years, watching him limp over to her.

“Got to go,” he said, nodding.

He hugged her for a long moment, outside the bathroom with the missing door, head full of anxiety. He knew what awaited him on the other side of the drive. Another impossibly difficult conversation with his provider, who, scared by the rising number of opioid prescribers facing criminal prosecution, would soon close the pain clinic. Another cut in his dosage in preparation for that day. More thoughts of the Glock.

The story of prescription opioids in America today is not only one of addiction, overdoses and the crimes they have wrought, but also the story of pain patients like Kenyon Stewart and their increasingly desperate struggles to secure the medication. After decades of explosive growth, the annual volume of prescription opioids shrank 29 percent between 2011 and 2017, even as the number of overdose deaths has climbed ever higher, according to the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science, which collects data for federal agencies. The drop in prescriptions has been greater still for patients receiving high doses, most of whom have chronic pain.

Opioid dosages at a 10-year low

Prescriptions per 100 people

All dosages

72.4

66.5

11.5

High dosage

6.1

2006

2016

Source: QuintilesIMS Transactional Data Warehouse, Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention

THE WASHINGTON POST

The correction has been so rapid, and so excruciating for some patients, that a growing number of doctors, health experts and patient advocates are expressing alarm that the race to end one crisis may be inadvertently creating another.

“I am seeing many people who are being harmed by these sometimes draconian actions amid this headstrong rush into finding a simple solution to this incredibly complicated problem,” said Sean Mackey, the chief of Stanford University’s Division of Pain Medicine. “I do worry about the unintended consequences.”

Chronic pain patients, such as Stewart, are driving extraordinary distances to find or continue seeing doctors. They are flying across the country to fill prescriptions. Some have turned to unregulated alternatives such as kratom, which the Drug Enforcement Administration warns could cause dependence and psychotic symptoms. And yet others are threatening suicide on social media, and have even followed through, as doctors taper pain medication in a massive undertaking that Stefan Kertesz, a professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who studies addiction and opioids, described as “having no precedent in the history of medicine.”

The trend accelerated last year, in part as a result of guidelines the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published in 2016. Noting that long-term opioid use among patients with chronic pain increased the likelihood of addiction and overdose, and had uncertain benefits, they discouraged doses higher than the equivalent of 90 milligrams of morphine.

The rise and fall of opioid prescriptions in the U.S. since 1992

Prescribed morphine milligram equivalents, in billions

240.3

170.7

25.4

1992

2011

2017

Source: IQVIA Institute for Human

Data Science

THE WASHINGTON POST

The guidelines, criticized as neither accounting for the differences in how quickly patients metabolize opioids nor addressing clearly enough what to do about patients who were receiving more than 90 morphine milligrams, helped open a new era of regulation. Dozens of states, Medicare and large pharmacy chains such as CVS have since announced or imposed restrictions on opioid prescriptions. The Justice Department, in a continuing push to crack down on pill mills and reckless doctors, announced in January that it would focus on providers writing “unusual or disproportionate” prescriptions. And some physicians, fearful of the financial and legal peril in prescribing opioids, and newly aware of their hazards, have stopped prescribing them altogether.

“We have to be careful of using a blunt instrument where a fine scalpel is needed,” said former surgeon general Vivek H. Murthy, who prioritized the opioid crisis during his tenure, and wants to increase access to alternative treatments. “We already experienced a pendulum swing in one direction, and if we swing the pendulum in the other direction, we will hurt people.”

Stewart, who said he hurt more every day, let go of Tyra. “See you Friday night,” he whispered to her. “Like always.”

He went outside to his truck. He checked for the third time that his near-empty pain medication bottles were in his duffle bag. Zipping the bag, he sighed. What he had left — five pills — would never last him until his next refill, two days from now. The pain, the withdrawal: All of it was only hours away. It would hit during the drive. He knew it.

How much longer could he keep doing this? How much longer could he afford to blow $900 a month — on gas, food, two nights in a motel, and pills for which he had no insurance? How much longer could he drive so many miles for less and less?

Something had to change.

But for now he started the truck, pulled out onto the mountain road, and then one mile was down, and there were 366 to go.

have shown they’re twice as likely to commit suicide, and what little research has been done on forcibly tapering opioid regimens has been troubling. One study, published last year in the journal General Hospital Psychiatry, tracked 509 military veterans involuntarily taken off opioids. It reported that 12 percent had suicidal ideation or violent suicidal behavior, nearly three times the rate of veterans at large.

She also knew about the hysteria in online chronic-pain forums. People were threatening to kill themselves because they couldn’t get medication. News articles about pain patients who had done it were being passed around on the Internet. “My wife committed suicide in October as a direct result of this,” said Wes Haddix, a retired dentist in Charlottesville. One doctor, Thomas Kline of Raleigh, N.C., recently came out of retirement and is reaching out to suicidal pain patients. “They write me, ‘Help me, I’m going to kill myself. What can I do?’ ” he said, echoing conversations that were ongoing in Wedvik’s office, too.

Some discussed it overtly: “I’ll be here for six months,” one man had said, “and then I’ll commit suicide.”

Others subtly: “I don’t want to kill myself,” said Karla Friend, a slight woman of 54 years. “But . . .”

Then there were patients such as Kenyon Stewart. Wedvik didn’t know about the Glock. But when he came into her office later that day, and was looking at her from across the desk, eyes red, hair disheveled, leg shaking, she knew something was very wrong.

“Can we have a talk?” Stewart said.

finding a doctor guilty of five federal drug charges, including conspiring to possess and distribute prescription opioids.

In Pennsylvania, the governor was absorbing criticism that he wasn’t combating the opioid crisis after he vetoed a bill that would have regulated drug prescriptions for injured workers.

In Montana, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions was telling an audience in Billings that doctors prescribed too many opioids, and that “we’re going to target those doctors.”

And meanwhile, in Washington state, on the side of a mountain 48 miles south of the Canadian border, Stewart was putting two bottles stuffed with opioids into his pocket and heading into his trailer.

“I missed you,” he said, hugging Tyra. “I missed you so much this time.”

He let her go and went into his bedroom, overrun with things that fit in their old house but not here. He reached up into the closet and placed the pills in an alcove at the top of his closet, where he thought nobody would think to look. He changed into shorts, grunting in pain, then went outside to look at the trailers along the dirt road.

Tomorrow, he would wake early and divide his medication, placing the week’s tapered ration into a plastic baggie. He would get on the computer and unsuccessfully try to buy kratom, which Wedvik had recommended. He would consider the Glock, then push the thought out of his head. “It’s going to be hard,” he would tell Tyra of what awaited, and she would respond, “We’ve been through worse.”

But in this moment, he kept looking out into the valley, the mountain casting a long shadow across half of it.

An elderly neighbor came out and saw him.

“Did you just get back?” she asked, and he nodded.

“Got to go back again?” she asked.

“No more,” he said, turning to head back inside. “I’m done.”

He limped for the stairs and closed the door behind him, as the shadow outside began to move across the rest of the valley.

‘I don’t know how you got this way:’ A young neo-Nazi reveals himself to his family

After the 2016 election, Kam Musser went from supporting white supremacists to joining a neo-Nazi group. And now his mother and grandmother wonder whether they can get him back.

Some say people on disability just need to get back to work. It's not that easy.

Lisa Daunhauer wanted to be one of the few to get off benefits. But first she had to succeed at Walmart.