- Joined

- Oct 11, 2016

- Messages

- 1,305

- Reaction score

- 2,233

Paper in JAMA last week:

jamanetwork.com

jamanetwork.com

So, the whole point of the ED-ICU is to improve the care of patients that cannot get a bed in an actual ICU. What I fail to understand is, why spend money building an “ED-ICU” when you could spend the same money building more ICU beds? Is it for some reason cheaper to build an ICU in the ED? Though, I don’t see why that would be the case.

What’s the point?

Association of an Emergency Department–Based ICU With Survival and Inpatient ICU Admissions

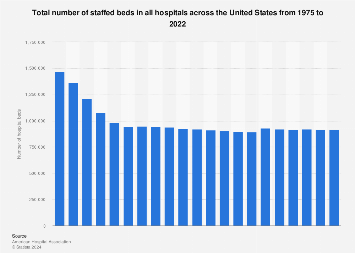

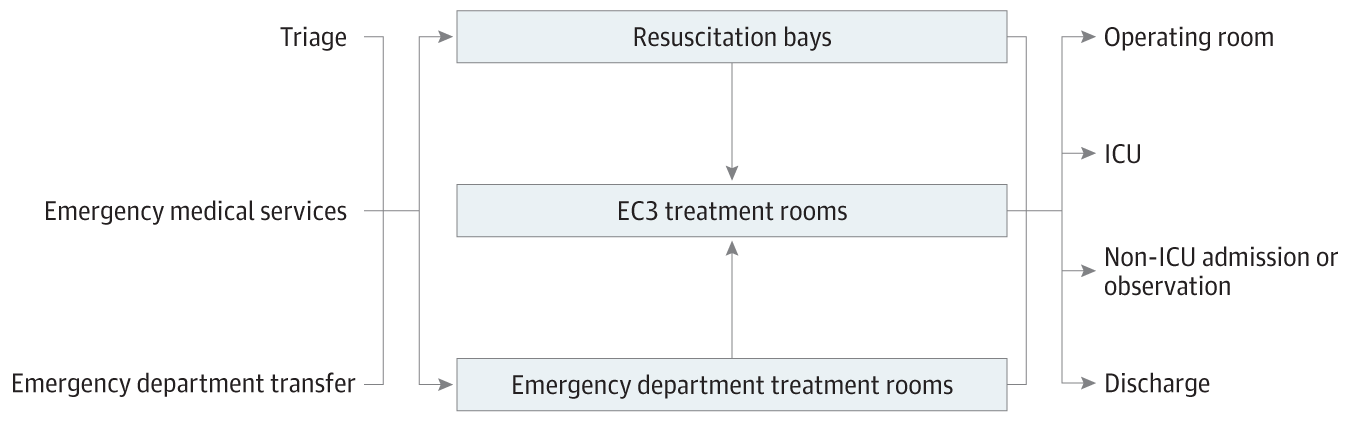

This cohort study compares 30-day mortality and inpatient intensive care unit (ICU) admissions before and after the implementation of a novel emergency department–based ICU.

So, the whole point of the ED-ICU is to improve the care of patients that cannot get a bed in an actual ICU. What I fail to understand is, why spend money building an “ED-ICU” when you could spend the same money building more ICU beds? Is it for some reason cheaper to build an ICU in the ED? Though, I don’t see why that would be the case.

What’s the point?