- Joined

- Oct 11, 2007

- Messages

- 2,348

- Reaction score

- 4,339

Over past few years, I have submitted to several NIH RFIs a similar idea based upon my experience reviewing K99/R00 and other mechanisms. Here is part of a slide I presented at the AAMC MD/PhD section meeting in DC, in the 50th anniversary of the MSTP mechanism in 2014:Unrelated to the broader discussion, but if I was NIH Director and interested in bolstering the physician scientist pathway, I would create grant mechanisms awardable to graduating MD/PhDs to establish small but longitudinal research projects throughout residency. Like enough money to hire a tech, buy materials, produce 1 high impact paper or preliminary data and be taken on as a fellow in an established, larger lab at an academic center for the duration of clinical training. Awardees would be allowed to integrate leading this project in a role more akin to that of a PI than a postdoc, but likely a bit of both, during their clinical training. Up to clinical departments and the awardee how they want to split the time / organize things.

The goal? Financial and time support to begin to produce preliminary data +/- papers for applying for a K immediately at the end of clinical training. Less time away from science, a clear recognition of the benefit physician scientists bring to science, training in the PI role while still not being complete independence, faces the reality of doing modern science in that things take much longer than they used (and at least in the wet lab it might make more sense to run a project at 50% effort for 2 years than 100% effort for 1) to in most disciplines and might bring down that "average age to R01" number,

...

NIH:

•Incorporate summer R25 URM/DV mechanisms for EVERY MSTP and competitively MD/PhD programs (Pipeline downstream).

•Incorporate institutional 2-year Transition Career Development Award (K22) program (mixed with individual K99/R00 applications) for PSTP support for EVERY CTSAs (Pipeline downstream).

Summer Gateways --> MSTP --> PSTP --> KL2(CTSA)

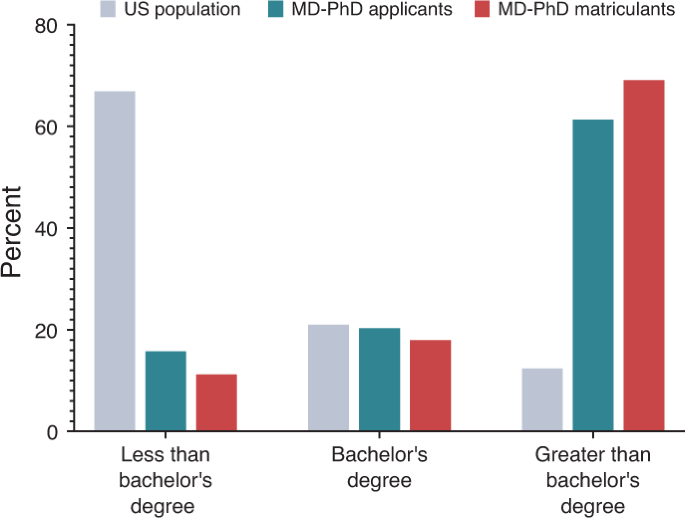

Barking, barking, barking... The NIH T32 should have FUNDING and a requirement for every MSTP to develop our untap underrepresented groups such as URMs, first-generation, etc.