- Joined

- Nov 16, 2017

- Messages

- 187

- Reaction score

- 364

This is both shocking and not.

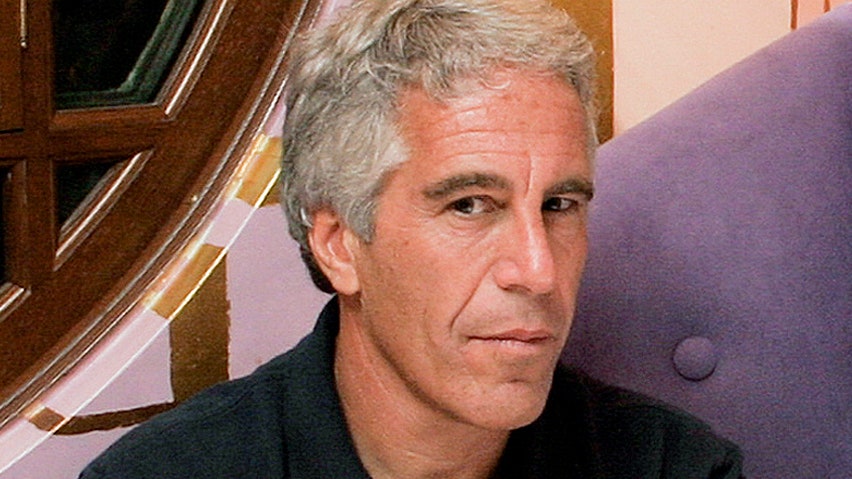

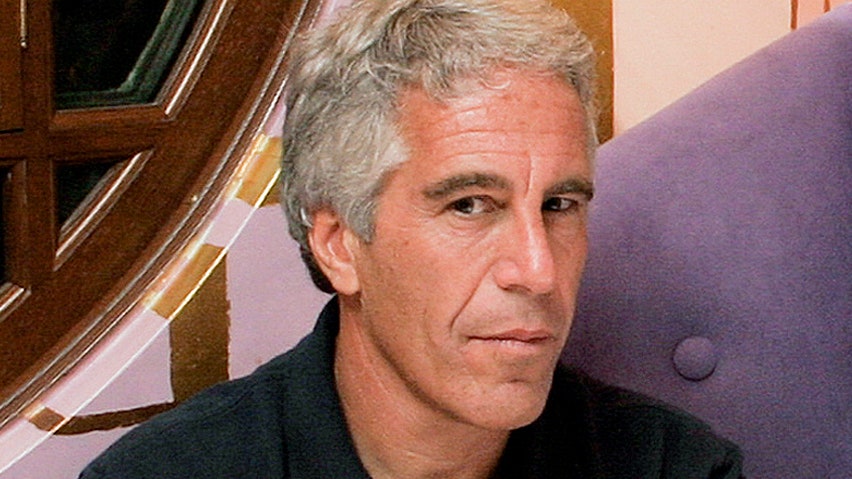

Jennifer Freyd PhD has done great research on the concept of institutional betrayal. In this case, it applies not only to the original victims of Epstein’s crimes, but also to the men and women in the Media Lab who unwittingly used his money for their research, were ignored when they learned of the relationship and complained, etc. The impact ripples out to other communities and individuals ad infinitum.

Beyond research, I am wondering if psychology as a profession can/should be doing more on the direct intervention side in addressing this particular brand of systemic rot in academia.

Do others know of psychologists who are doing this type of work?

www.newyorker.com

www.newyorker.com

Jennifer Freyd PhD has done great research on the concept of institutional betrayal. In this case, it applies not only to the original victims of Epstein’s crimes, but also to the men and women in the Media Lab who unwittingly used his money for their research, were ignored when they learned of the relationship and complained, etc. The impact ripples out to other communities and individuals ad infinitum.

Beyond research, I am wondering if psychology as a profession can/should be doing more on the direct intervention side in addressing this particular brand of systemic rot in academia.

Do others know of psychologists who are doing this type of work?

How an Élite University Research Center Concealed Its Relationship with Jeffrey Epstein

New documents show that the M.I.T. Media Lab was aware of Epstein’s status as a convicted sex offender, and that Epstein directed contributions to the lab far exceeding the amounts M.I.T. has publicly admitted.

Last edited: