This has been discussed ad nauseam on this forum. See

I'm a 3rd year interested in psych and I'll admit the whole unknown realm of anti-depressants is a bit of a turn off for me. How can something so generally prescribed as SSRIs be something that has a success rate on par with placebos for most cases of depression? Why are they still being used...

forums.studentdoctor.net

This may be kind of a dumb question for a PGY-3, but what are we actually doing with anti-depressants? A family debate recently had me looking more into this again, and I'm pretty surprised to see how little of an effect over placebo they have...and that even the measured effect is a rather...

forums.studentdoctor.net

The most succinct and accurate summary is a comment in the second thread:

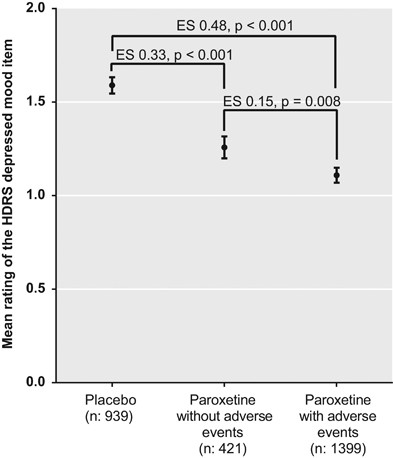

"Antidepressants have an effect size of 0.3. Proponents and opponents argue whether that counts as "working.""

It seems important to note that the effect of placebo is estimated to be a reduction of an estimated 8.3 points on the HAM-D vs. a reduction of about 10.1 on the HAM-D for antidepressant medications. I think the recommendation by the authors of the most recent review is telling:

The aim of this review is to evaluate the placebo effect in the treatment of anxiety and depression. Antidepressants are supposed to work by fixing a chemica...

www.frontiersin.org

What Is to Be Done?

How then shall we treat depression?

One suggestion that has been made to me informally is to prescribe antidepressants as active placebos. An active placebo is a pharmacologically active substance that does not have specific activity for the condition being treated. Antidepressant medications have little or no pharmacological effects on depression or anxiety, but they do elicit a substantial placebo effect. Could we not use them as a means of capitalizing on the power of placebo?

The problem with this suggestion is that treatment decisions need to be based on an assessment of risks, as well as benefits. The risks of antidepressant treatment include suicidal and violent aggressive behavior in adolescents and young adults; stroke, death from all causes, falls and fractures, and epileptic seizures in the elderly; and sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, diabetes, deep vein thrombosis, and gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding in everyone else (

55–

62). One might argue that these risks might be worth taking for an effective treatment of severe depression, but are they worth risking for a treatment that has no benefit at all over placebo for first-time users?

A second possibility would be to prescribe placebos. They are safe and effective, with relatively few nocebo side effects and no health risks. The problem with prescribing placebos rests with the commonly held assumption that to be effective in clinical practice, placebos have to be presented deceptively as active medications. This assumption has been reported to be false in recent clinical trials [reviewed in Ref. (

63)]. In these studies, placebos were presented non-deceptively as placebos with no active ingredients. How could this ever work? The answer is that it was accompanied by a rationale in which it was explained that placebos have been found effective to the condition being treated, that it has been found to involve Pavlovian conditioning, and that it might therefore be effective in treating the person’s condition. This rationale has been found to be critical for the success of the open-label placebo (OLP) intervention (

64). Additional OLP trials with larger samples, longer duration, and blinded assessors are warranted.

Unfortunately, only one of the studies assessing OLPs involved the treatment of depression, and that one, although showing promising results, was only a small pilot (

65). However, there are many other treatments that equal antidepressants in terms of degree of symptom reduction (

66–

69). These include psychotherapy, physical exercise, acupuncture, omega-3, homeopathy, tai chi, qigong, and yoga. We do not know the mechanisms of these alternative treatments, and their efficacy may be at least partly due to expectancy, but they are certainly safer than antidepressant medication.

The long-term advantage of psychotherapy over medication has been shown in a number of studies [reviewed in Ref. (70)]. Whereas short-term outcomes were equivalent between the two treatments, long-term outcomes were significantly better for patients who had received psychotherapy than for those who had received medication. Additionally, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program reported relapse rates of 36% and 33% for cognitive behaviour therapy and interpersonal therapy, respectively, compared with a 50% relapse rate for antidepressant medication (

71). However, the rate of relapse for patients who had recovered on placebo was 33%, the same as that for psychotherapy. There are two take-home messages from these data. First, it dispels the myth that placebo responses are short-lived. Second, it raises the questions of whether psychotherapy reduces relapse or medication increases it (

72).

Support for the hypothesis that antidepressant medication increases the risk of relapse comes from other studies comparing antidepressant and placebo treatment for depression and anxiety disorders. Consistent with the NIMH data, a 2011 meta-analysis reported a relapse rate of 25% for depressed patients successfully treated with placebo compared to relapse rates ranging from 42% to 57% among those treated with various antidepressants (

73). A direct test of the effect of antidepressants and psychotherapy on the risk of relapse comes from a study on the treatment of panic disorder (

74). The study compared the 6-month relapse rates for patients who had been treated with a tricyclic antidepressant (imipramine), cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), or the two combined. The results, displayed in

Figure 4, indicate that the risk of relapse following imipramine was more than double that following CBT. However, the addition of the antidepressant to imipramine completely erased that benefit. Similarly, physical exercise as a treatment for depression has been shown to have a much lower relapse rate than SSRIs, but that benefit disappears when the two treatments are combined (

75).

These studies reveal another benefit of including placebos in clinical trials of medication. They can reveal situations in which the treatment does more harm than good for the condition being treated. For example, placebos have outperformed antipsychotic medication (haloperidol and risperidone) in the treatment of delirium in palliative care patients and aggression in intellectually disabled adults (

76,

77). Similarly, placebo was significantly better than a combination of chondroitin and glucosamine in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis (

78) and showed similar superiority in a trial of nutraceuticals in the treatment of depression (

79).

Given these data, I suggest that the following principles be used in treatment selection. When treatments are equally effective, recommend the safest. When they are equally safe, let the patient choose which he or she prefers. Before making this choice, however, patients should be accurately informed of the potential harms of antidepressant medication (e.g., increased risk of relapse, suicidality, gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, diabetes, stroke, epilepsy, and death from all causes), as well as the finding that all of these treatments appear to be equally effective in the short term but that psychotherapy and physical exercise might be more effective than antidepressants in the long run."

I have yet to meet a psychiatrist who talks about or thinks about their prescription of antidepressants as "an active placebo", and yet that's what the evidence seems to suggest. I've also never heard anyone suggest prescribing a nocebo, but again the evidence supports that. And finally I've only very rarely heard an MD say their first-line response was the safest and most effective recommendation for patients reporting depression symptoms: psychotherapy.

It's hard to look at this research and not wonder if med management for depression is in many cases a more sophisticated and modernized mesmerism.