Is that to me or are you making a general comment? Chance of funding success ranges from very low for some individuals to very high for others depending on who they are, who is supporting them, where they can get money from, etc so looking at the NIH average without taking into account individual circumstances is not very useful. Different people will have different definitions for what is reasonable.

Well, now you are talking about a precision medicine issue. We need the estimate of the average effect size first. Subgrouping would require additional predictors. So the data point is quite the opposite of "not very useful." It's foundational.

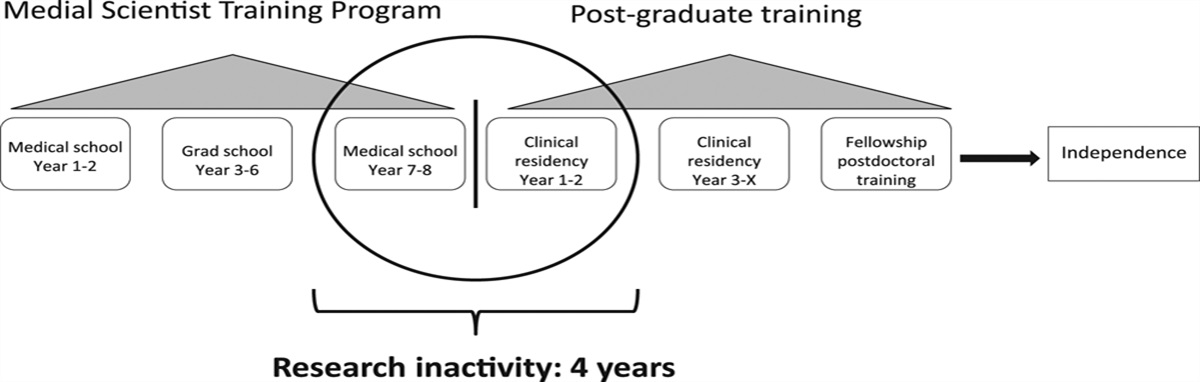

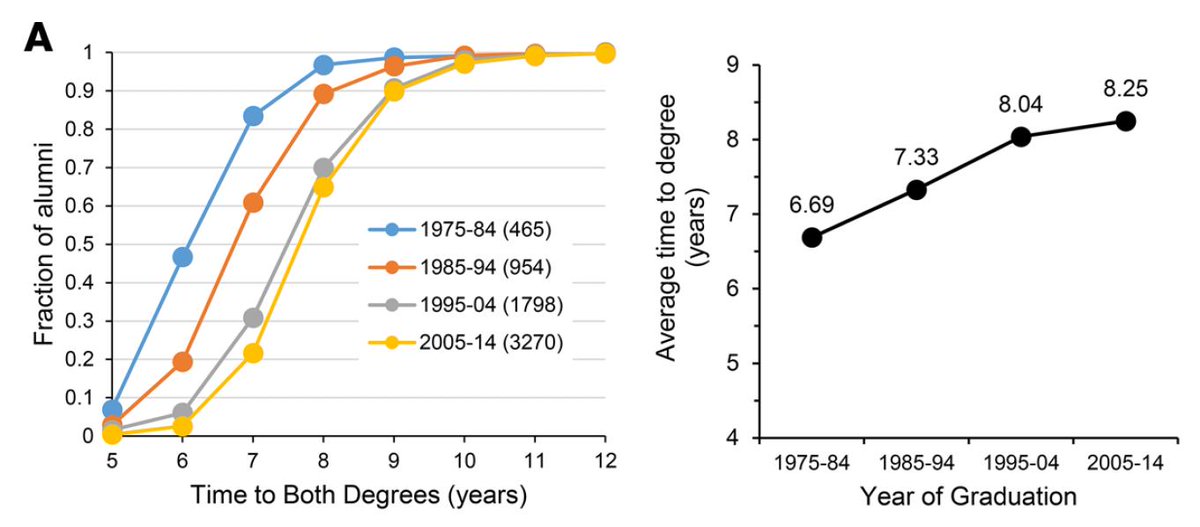

What is "failing"? You're not only trained as a researcher, half of your time is training to be a clinician. Even MD-only students do research or even research year(s). Both degrees are terrific preparation for many career paths. It's 8 years of free tuition and small stipend to do something you presumably enjoy.

In program evaluation, metrics need to be pre-specified. There's a tendency to use euphemisms to hedge your program's success when it's clearly failing. The problem here isn't that the program is producing one outcome or another, it's that the intended outcome isn't the one that's being measured or evaluated against. E.g. you apply for approval for a medication to the FDA, and it has no mortality benefit. And now you step back and say that it should be approved based on secondary outcomes like "life satisfaction".

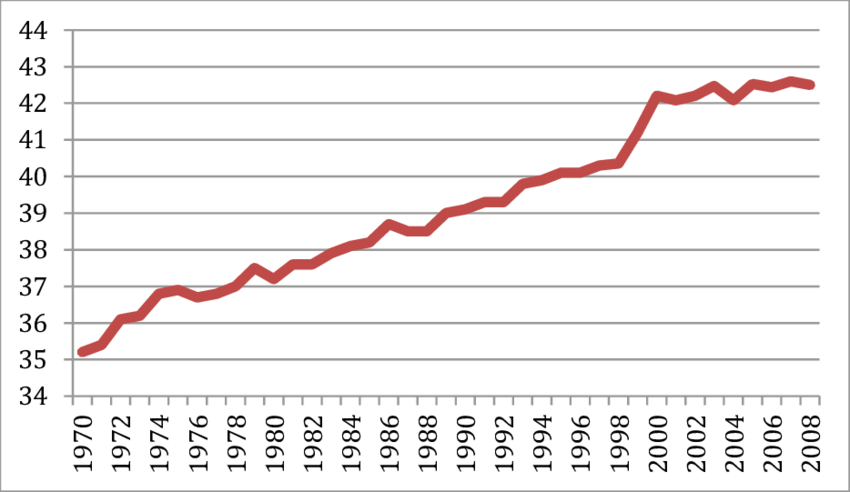

I want to know the cold data on whether there IS mortality benefit before you go out there and spill a bunch of salesmanship to me. It turns out there IS a benefit for getting an R01 if you have MD-PhD vs. MD vs. PhD, but the absolute effect size is small. (call it 3-5%, against a background rate of 15%). The relative effect size is large [obviouisly]. Me as the subject matter expert (which I actually can reasonably claim, as this is one of those things I followed around and in fact published a paper on) would say okay this makes me give a stamp of approval to MD-PhD.

My recommendation to policymakers would be actually to radically drop the number of PhD programs and increase the number of MD-PhD programs. I actually think most PhDs in biomedical research are more interested in translational questions from the get-go, but high end publications/labs actually are functionally against translational questions. This then trains the translational mind out of youths, which is a terrible mistake. Furthermore, we have a physician shortage, and a scientist excess.

Of course, I got ****storm for this on Twitter. LOL PhDs are so scared of not getting a job outside of science that they'd rather not have their postdoc spots cut. Fine--keep drinking the coolaid and die a miserable impoverished death.

Thank you for sharing your perspective

@ChordaEpiphany ... While I still remain more idealistic than you seem to be, your point-of-view is valid, reasonable, and might be representative of many others who we lose in the PSW path. Your request of

"find ways to inject dignity and security back into the pathway

" is a Systems-Based Practice issue that is

not easily addressable by a single training director or individual. The

luxury chocolate market is a tough business... nice analogy! The Holiday season is coming up, and then it is Valentine's day. Your business model must be predicated on burst sales with many dry months. Even K awards can travel. When you get it, it is your point of maximum leverage to get the most protected time (w salary) in negotiation. There are skill sets not taught during MD-PhD training that are critical for successful transition into academic medicine. At the very least, this

HHMI pdf book should be required reading.

It's addressable, and some versions of it you've already pointed out yourself:

1. the job would be a high-end luxury item, which means it's not scalable.

2. the job would be high paying, guaranteed, and extremely selective. At Rockefeller, not only is your salary guaranteed, your lab has a floor budget even if you lose federal funding. Think about that.

3. the job would be associated with other luxury things (i.e. named fellowships, endowments, famous professors, fancy publications, etc)

There are instructions in the country where such jobs are sponsored (i.e. Rockefeller, Whitehead, etc.)

The University of Texas could start sponsoring these jobs, and it's almost guaranteed that you'll start to get luxury candidates.

3 grants a year at 15% from the feds is the opposite of luxury. It's the definition of white-collar factory work. Which is fine, for some...most people are fine with Macy's.